INTRODUCTION

Social media is ubiquitous and has dramatically altered who controls a brand’s narrative. Brand content, which was once the province of advertisers, is now created and shared by community members within a brand’s social media ecosystem (Peltier et al., 2020). There is a growing stream of conceptual and empirical research exploring the antecedents of social media usage (Vander Schee et al., 2022). However, the extant empirical literature has largely ignored important motivational drivers of the quantity and valence of information sharing behaviors (Gardner et al., 2022; Peltier et al., 2023; Schaefers et al., 2021), and even less is understood regarding how social media leads to electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM). These are critical omissions in the social media and brand engagement literature (Ismagilova et al., 2020; Swani & Labrecque, 2020).

As an extension of brand attachment theory, recent research has explored how consumers’ attachment to social media impacts self–brand connections and brand advocacy behaviors (VanMeter et al., 2018). Social media attachment has been conceptualized in terms of bond strength between consumers and social media and reflects the degree to which social media is weaved into consumers’ lifestyles as a form of impression management (VanMeter et al., 2015). Viewed this way, consumers with higher social media seek to fulfill desired self-identities, built and reinforced via the content with which they engage and share with others in their peer-to-peer social communities (Harrigan et al., 2018). Noting a lack of appropriate scales, Baboo et al. (2022) developed and validated an eight-dimension social media index. While this index and other emergent studies offer value when considering social media as a global measure of attachment to varied social media platforms (de Oliveira Santini et al., 2018; Ismagilova et al., 2020), little conceptual and empirical research has investigated the antecedents of consumer attachment to a target brand’s social media and how this attachment leads to brand advocacy and eWOM behaviors (Sánchez-Fernández & Jiménez-Castillo, 2021; Wright et al., 2017). This is an important distinction because the antecedents and consequences of social media in general versus attachment to a target brand’s social media are likely to vary (Harrigan et al., 2018; Vander Schee et al., 2020; Voorveld et al., 2018).

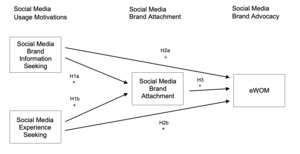

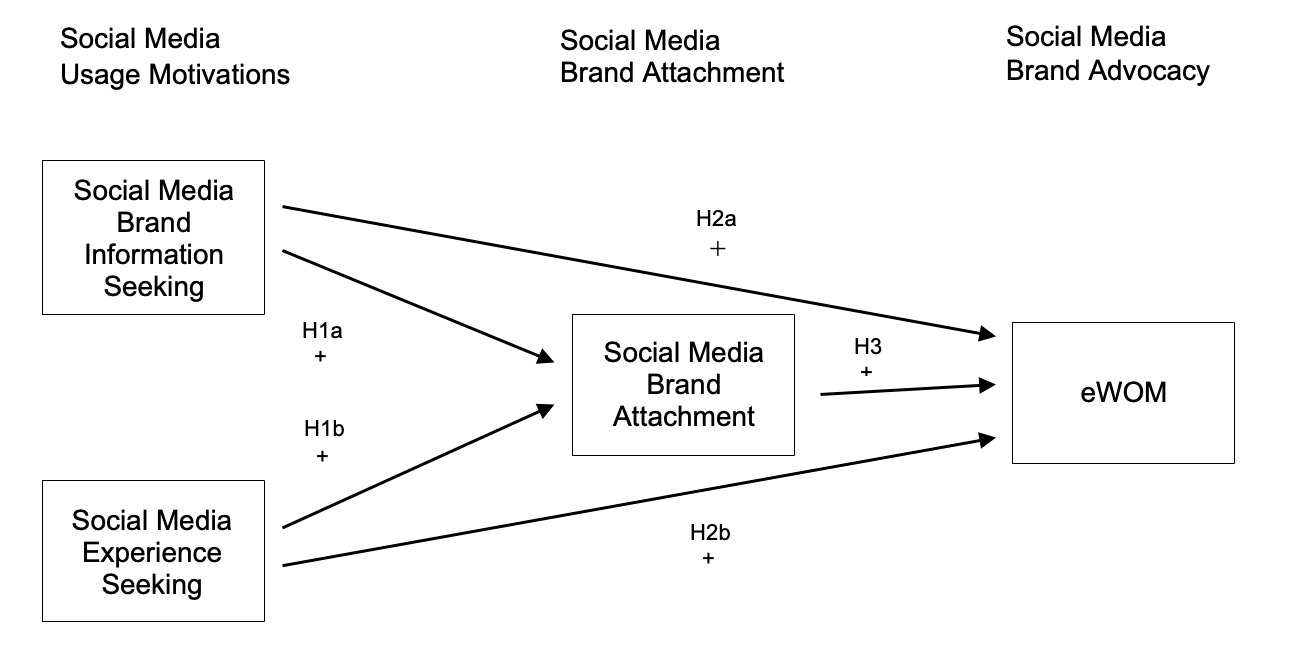

Given these research gaps, using attachment theory, the authors conceptualize and empirically investigate a structural framework for understanding how social media usage motivations impact attachment to a target brand’s social media and, in turn, eWOM brand advocacy (see Figure 1). The authors investigate two potential motivations driving brand-specific social media, namely, social media brand information-seeking activities (Baboo et al., 2022; VanMeter et al., 2015) and social media experiential seeking activities (Voorveld et al., 2018). Our study contributes to marketing literature in several ways. First, responding to the calls by Gardner et al. (2022) and Hemsley-Brown (2023) and Peltier et al. (2024), we investigate how brands and social media interact in the evolving digital era, specifically focusing on the new generation of digital natives.

Extending social media theory (Baboo et al., 2022), we develop and validate a scale for measuring brand-specific social media, which to the best of our knowledge is missing in literature. Our scale allows researchers to investigate theories and constructs that may impact attachment to a brand’s social media initiatives. Further, our findings support that social media usage motivations are important antecedents of brand-specific social media. Lastly, using structural equation modeling, our exploratory findings extend the literature through an increased understanding of how eWOM brand advocacy is influenced within social media ecosystems, specifically the critical roles social media usage motivations and attachment to a target brands’ social media efforts play in this process (Peltier et al., 2024). Surprisingly, while social media brand attachment partially mediates the relationship between usage motivations and eWOM, experience seeking has a direct, negative effect.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory has its conceptual genesis in the developmental psychology literature, initially focusing on interpersonal and social bonds between children and their caregivers (Bowlby, 1969, 1988). Attachments formed through close, personal relationships with others create security via feelings of affection, passion, and dependency (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Given this life focus, (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2005, p. 27) defined attachment style as a person’s “systematic pattern of relational expectations, emotions, and behaviors that results from a particular history of attachment experiences.” Although relatively new to consumer research, studies have utilized attachment theory to understand relationship bonds not only for individuals but also other attachment targets (e.g., products, websites, institutions, formal and informal groups, brands, celebrities, social media).

Brand Attachment Theory

Recently, consumer researchers have extended the focus of attachment to include the strength of bonds consumers have with brands, including experiential (e.g., sports teams, influencers, celebrities) and product-based (e.g., consumer electronics) attachment targets (M.-S. Park et al., 2019). Consumer attachment is essential because someone emotionally connected to a brand is likely to feel that the brand is irreplaceable (Hemsley-Brown, 2023). (C. W. Park et al., 2010, p. 2) defined brand attachment as “the strength of the bond connecting the brand with the self.” Brand attachment has been conceptualized in many ways, including the strength of the cognitive and affective bonds that connect the individual with a brand (C. W. Park et al., 2010), brand identity (Fayed, 2024), brand resonance (Husain et al., 2022), emotional brand connections (Hemsley-Brown, 2023), brand-related feelings and relationship with the self (Shimul, 2022), and brand affection, connection, and passion (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Research has shown self–brand connections are stronger when there is congruence between a target brand’s external identity and a consumer’s self-identity (Harrigan et al., 2018; Panigyrakis et al., 2020). Recent research has found that brand attachment is positively associated with a variety of consumer outcomes, including brand usage (Shimul, 2022), purchase intention (Schaefers et al., 2021), information sharing (Zhang & Patrick, 2021), promoting or defending a brand (Jami et al., 2021), brand advocacy (Hemsley-Brown, 2023), eWOM (Chen & Lu, 2024), and attitude toward the brand (Hung & Lu, 2018).

Social Media Attachment Theory

A growing stream of research has suggested that consumers’ attachment to social media as a communication platform leads to positive behavioral outcomes such as general attitudes towards social media, increased social media usage, information creating and sharing, advocacy, and eWOM (Algharabat et al., 2020; VanMeter et al., 2018). Extending attachment theory, (VanMeter et al., 2015, p. 71) defined social media as “the strength of a bond between a person and social media.” Consistent with attachment theory, Swani and Labrecque (2020) contended that consumers use social media for impression management and personal branding purposes; stronger social media occurs when users feel that a specific social media platform, or social media in general, allows them to craft identities congruent with their desired social identities and offers content that is both engaging and has value for sharing with others. As with brands, social media is enhanced through stronger self–site connections, greater affective and emotional commitment, and feelings of digital intimacy (Ismagilova et al., 2020; M.-S. Park et al., 2019).

While extant literature has begun to examine what drives attitude toward social media and usage, research investigating how to conceptualize and operationalize social media as a theoretical construct is in its infancy (Baboo et al., 2022; Li & Xie, 2020). VanMeter et al. (2015) developed a social media scale with eight dimensions: connecting, nostalgia, informed, enjoyment, advice, affirmation, enhances my life, and influence. Using this scale, social media had a strong positive effect on social media advocacy (e.g., recommendations and eWOM) and social media supportive behaviors (e.g., offering brand advice). Using a comprehensive qualitative–quantitative approach, Baboo et al. (2022) developed and validated an eight-item social media scale with the following conceptual sub-dimensions: connecting or socializing, keeping up to date, dependence, dysfunctional use, expressing feelings, self-presentation, seeking self-esteem, and seeking knowledge.

Social Media Brand Attachment

As an emerging theoretical construct, social media theory focuses on how attachment to social media in general is established and how it may impact brand advocacy and other important behavioral measures (Baboo et al., 2022; Peltier et al., 2023). Pertinent to the current study, there is interest in how social media usage motivations impact attachment to a target brand’s social media and, in turn, their advocacy behaviors. To date, there has been only limited conceptual and empirical research related to brand-specific social media (Sánchez-Fernández & Jiménez-Castillo, 2021). Although not framed as brand-specific social media, VanMeter et al. (2018) outlined two brand behaviors on social media: token and meaningful behaviors; token behaviors relate to more passive brand behaviors such as viewing and liking a brand’s social media, while meaningful behaviors are more active in nature, including brand information, brand usage, and brand advocacy. Investigating consumer engagement for a brand’s website, Harrigan et al. (2018) found that consumers’ self–brand connections with the website positively impact brand usage behaviors.

Extending this work, Vander Schee et al. (2020) proposed that attachment is a consumer disposition that may drive content consumption, contribution, and creation regarding desired social media brands, which may then influence six brand outcomes: brand connection, brand disposition, brand affirmation, brand status, brand attributes, and brand aversion. Using attachment theory, including brand attachment and social media, social media brand attachment is defined here as the strength of an individual’s relational bonds and emotional connections associated with a target brand’s social media platforms and messaging content.

Antecedents of Social Media Brand Attachment

While consumers have relationships with social media, advertisers are more interested in increasing attachment to their brand-specific social media platforms, profiles, and messaging initiatives (Panigyrakis et al., 2020). Embryotic research has suggested that like social media, consumers engage with a target brand’s social media as a form of impression management (Swani & Labrecque, 2020). It is expected when a target brand’s social media platforms allow consumers to establish and build desired social media self-identities, it will create strong self–site connections (Ismagilova et al., 2020; M.-S. Park et al., 2019). Given this, information sharing allows consumers to find and create brand content needed to convey a sense of self-connection to a brand’s social media, especially when there is information–self–brand congruence (Ye et al., 2021). Along this line of reasoning, engaging in information- and experience-seeking activities provides consumers with foundational knowledge and experiential resources needed to understand self–brand congruence (Baboo et al., 2022; de Oliveira Santini et al., 2018; Vander Schee et al., 2021; VanMeter et al., 2015, 2018).

H1a: The motivation to seek social media information about brands positively influences social media brand attachment.

H1b: The motivation to seek social media experiences about brands positively influences social media brand attachment.

Social Media Brand Attachment and Usage Motivations

There is a well-established belief that consumers’ emotional and affective attachments toward a brand increase their advocacy behaviors (Dwivedi et al., 2019). Brand advocacy has been viewed as actively and voluntarily sharing positives recommendations of a brand to others (Shimul & Phau, 2023). Advocacy behaviors occur when consumers form emotional attachments with brands (Ahmadi & Ataei, 2022). The social media literature has most often operationalized brand advocacy as eWOM (VanMeter et al., 2015). Though eWOM has been conceptualized in many ways, in this study, brand social media eWOM is defined as the formal or informal support an individual communicates about a brand using social media platforms, including verbal, audio, pictorial, or video communications (Ismagilova et al., 2020).

When advocates use their social media networks to share advocacy-based communications supporting a target brand, they explicitly tie that brand to their self-identities and public personas (Swani & Labrecque, 2020). Although little research has investigated eWOM in the context of social media usage motivations and brand-specific social media, a meta-analysis by Ismagilova et al. (2020) found that social media eWOM is greater for consumers who seek and share information, who seek congruence with self–brand identities and self-enhance opportunities, who have a strong affective commitment to the brand, and who value experiences that open them up to new ideas and practices.

H2a: The motivation to seek social media information about brands positively influences target brand eWOM.

H2b: The motivation to seek social media experiences about brands positively influences target brand eWOM.

H3: Social media brand attachment positively influences target brand eWOM.

METHOD

Sample and Procedure

The survey was pre-tested with five business professionals who scrutinized the items for clarity and face validity. Their feedback provided the basis for editing and refinement in Qualtrics. A link to the survey was provided on the Brightspace platform for each course included in the study. The convenience sample of undergraduate students were enrolled in a marketing course at a Midwestern U.S. public university. As digital natives, these respondents represent Gen Z and the next generation of information seekers and brand advocates (Flight & Allaway, 2024). A total of 440 out of 586 students (75%) responded. Of these, 220 were randomly selected for the preliminary analysis. The remaining 220 were used as a validation sample. Table 1 provides the respondent profile. Respondents were told to consider their favorite brand when answering questions related to the constructs of interest.

Measures

Scales used in the survey were adapted and extended from the extant literature. All survey items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). See Table 2 for scale items and standardized loadings. The minimal sample size threshold of 15 respondents per item for a total of 180 respondents, was exceeded by the 220 respondents included in the validation sample without over powering the results with an inflated sample size (de Winter et al., 2009).

The construct social media brand information seeking reflects an individual’s motivation to use social media to obtain information about specific products or brands. This was measured using six items adapted from Chahal and Rani (2017). The construct social media experience seeking embodies an individual’s motivation to use social media for personal enjoyment and experiential purposes. The three-item scale for this construct was adapted from Abrantes et al. (2013).

Social media brand attachment represents the strength of an individual’s relational bonds and emotional connections associated with a target brand’s social media platforms and messaging content. We reviewed the literature on brand attachment and social media to develop an initial list of 14 scale items reflective of social media brand attachment. Following a pilot test, the authors removed two items due to low factor loadings in an exploratory factor analysis (Nunnally, 1978), leaving a 12-item social media brand attachment scale based on the concepts of social media, brand attachment, brand involvement, brand intimacy, and self–brand connection (Gómez et al., 2019; Harrigan et al., 2018; Simon & Tossan, 2018). Only minor wording revisions were made to items utilized from other scales such as This brand’s social media reflects who I am (Harrigan et al., 2018) became This brand’s social media represents who I am.

Finally, eWOM reflects individuals’ non-compensated social media advocacy for their favorite brands, as measured by a four-item scale associated with brand fidelity and brand loyalty (Grace et al., 2020; Roy et al., 2014). Students evaluated the statements based on social media eWOM activities.

RESULTS

Measurement Model

Prior to hypothesis testing, a composite confirmatory factor analysis using Smart PLS 3 was conducted to assess the measurement model (Table 3). All standardized regression coefficient loadings exceeded .7, composite reliabilities exceeded .80 for all constructs, and average variance extracted exceeded .5, establishing convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2013). The square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded all paired correlations shown in the diagonal of the correlation matrix, and all Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio correlations were less than 0.6, confirming discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2020). Table 3 provides the correlation matrix, reliability and validity estimates, and descriptive statistics.

Structural Results

Model hypotheses were tested using Smart PLS 3 with a bootstrap sample of 5,000. As shown in Table 3, as predicted, social media brand information seeking (H1a: β = .468, t = 7.1, p < .001) and social media experience seeking (H1b: β = .202, t = 3.1, p < .002) positively impacted brand-specific social media attachment. social media information seeking also positively impacted eWOM (H2a: β = .379, t = 6.0, p < .001). Unexpectedly, social media experience seeking (H2b: β = -.190, t = -2.9, p < .004) had a significant, negative impact on eWOM. Lastly, brand-specific social media attachment positively impacted eWOM (H3: β = .390, t = 5.8, p < .001). The R2 values for brand-specific social media attachment (.35) and eWOM (.38) both indicate a high level of variance explained. Once our model results were confirmed, we used our hold-out sample to assess the robustness of our empirical results, finding a similar pattern of results.

A key focus of our study is to assess the antecedents and consequences of social media brand attachment. Consequently, we also assessed whether social media brand attachment mediates the relationships between social media usage motivations (social media brand information seeking and social media experience seeking) and eWOM. We examined the specific direct, indirect, and total effects in Smart PLS 3 to confirm the mediation effects following the approach by Hair et al. (2022). As shown in Table 4, comparing the significance of the direct and indirect effects confirmed the mediation results. First, social media brand attachment has complementary, partial mediation effects between social media brand information seeking and eWOM (indirect effect: β = .181, p < .001). Additionally, a case of competitive partial mediation surfaced when examining the effects of social media experience seeking on eWOM (indirect effect: β = .080, p < .010).

DISCUSSION

Overall, we found that both of our social media usage motivation antecedents had significant, positive influences on social media brand attachment, providing evidence for the importance of informational and hedonic experiences from engaging with a firm’s social media branding initiatives. The theoretical value of our brand-specific social media attachment scale was also confirmed by showing its strong relationship with social media brand advocacy in the form of non-paid eWOM.

Surprisingly, while social media information seeking had a positive impact on eWOM, social media experience seeking had a negative relationship with eWOM. Our mediation findings clearly show that social media brand attachment is a key intermediary between social media usage motivations and eWOM. First, consumers motivated to use social media for information seeking are more likely to activate social media brand attachment that enhances consumers’ engagement in eWOM. Second, social media experience-seeking motivations have a more complex relationship.

Our findings suggest consumers motivated by social media experience seeking may engage in social media advocacy more for personal promotion rather than advocating on behalf of a brand. Identifying motivation may be related to the age cohort utilized in the study, commensurate with the findings identified by Florenthal (2019), where uses and gratifications theory can help to explain the apparent contradiction. At the same time, the brand’s social media presence and shared content may increase social media brand attachment for consumers.

CONCLUSIONS

Marketing scholars are showing an increased interest in understanding consumers’ attachment to social media in general, and more specifically, to a brand’s specific social media presence. Advancing the embryonic literature on consumer engagement and attachment to a brand’s social media efforts, the current study conceptualizes and empirically examines a framework for understanding how two different consumer motivations jointly influence the formation of consumers’ social media identities via social media brand attachment and ultimately impact consumer engagement in social media brand advocacy (eWOM).

Extending brand attachment and social media theory, our study is one of the first to introduce the concept of social media brand attachment and empirically validate its critical role in consumers’ eWOM. Our study contributes to the social media consumer engagement literature by conceptually defining and operationalizing social media brand attachment as a cognitive and affective component of consumer engagement. The findings of this study also highlight the quintessential nature of evaluating brand engagement’s cognitive and affective dimensions by showing how social media usage motivations contribute to a consumers’ self-identification with a brand’s social media.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Brands hoping to increase the effectiveness of their social media marketing may benefit from an increased focus on messaging and content that encourages sharing, thereby helping consumers realize and express their desired self-identity via a stronger attachment to the brand’s social media presence. Consumer participation can manifest as passive engagement behaviors such as likes or follows as well as more active behavior including sharing and contributing original content.

Brand managers should also focus their social media efforts on cultivating and supporting consumers’ self-actualization of their self-brand connection. Since consumers use their social media profile to express their identity, brands may help consumers communicate their individuality by providing media mechanisms for consumers to build a unique social presence. For example, brands offering badging or community standing recognition may help consumers publicly display their level of brand connectivity. This approach encourages engaged consumers to become broadcasters within a network of followers based on brand knowledge or user personality. Brands can foster relationships by providing engaging and relevant brand content for influencer consumption and dissemination. The ensuing symbiotic relationship between brands and influencers provides benefits for both. Influencers fulfill intrinsic motivation (Swani & Labrecque, 2020), while firms experience enhanced brand advocacy.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

As with all research, this study has limitations. Gen Z was the intended target audience; therefore, the survey was only administered to college students. Findings may differ with other age cohorts. All survey respondents were enrolled in a marketing course when they completed the survey and thus were likely to be a marketing or business-related major. Not having representation from majors in other disciplines could bias the results. All survey respondents were enrolled in a Midwestern public university. Experiences with social media may vary based on residency. The study was limited to survey responses. Future research could consider qualitative research approaches such as focus groups or ethnographic investigations to gain a more thorough understanding regarding motivations and behaviors.

Although this study contributes to the brand attachment and social media literature, more research is necessary that contributes to our understanding of brand social media and consumer brand engagement (Baboo et al., 2022; Sánchez-Fernández & Jiménez-Castillo, 2021). Research is necessary that examines the complex relationship between social media experience seeking motivations and eWOM. Consumers’ social media usage motivations may also evolve (Reisenwitz, 2021), going beyond the cognitive need for information to the more hedonic and social dimensions of interacting with others through social media experience. Thus, future research may investigate how social media usage motivations evolve, and how this affects social media brand attachment.

Given the essential nature of social media brand attachment, future research is necessary that explores this concept. The authors offer an initial conceptualization reflecting an individual’s relational and emotional bonds to a target brand’s social media presence. Future research may also investigate different conceptualizations of social media brand attachment, including multi-dimensional conceptualizations (Vander Schee et al., 2020). Marketing scholars will also benefit from understanding the different drivers and outcomes of social media brand attachment. For example, research that examines how specific messaging content and marketing strategies influence brand social media experience is warranted (Fayed, 2024). Future research should also explore the influence of diverse branding strategies on brand social media information seeking to help brands take a more active and intentional role in fostering influencer engagement. For example, the connection can be further explored with branding strategies such as social media trust (van Zoonen et al., 2024), social media post characteristics (Liu et al., 2024), social media storytelling (Coker et al., 2017), and social identity (Rawal & Saavedra Torres, 2017) to name a few.

Finally, social media sharing is a focal activity in brand engagement (Vander Schee et al., 2020) and is likely to range in a continuum from more passive, token behaviors (i.e., viewing, liking) to more active, meaningful behaviors (i.e., content sharing, creation) (VanMeter et al., 2018). Research that investigates how usage motivations, brand social media, and eWOM relates to the different manifestations of social media engagement is necessary. While extrinsic rewards are likely to play a primary role for paid social influencers (Tuncer & Kartal, 2024), knowing the degree to which organic (i.e., non-paid) consumer influencers are motivated merits further study (Smith & Chen, 2018). Likewise, developing a better understanding of how brand social media influences these consumers will help brands be more informed regarding the most appropriate and effective ways to engage influencers via advertising and other social media content.