Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically changed the way people shop, and one of the most notable changes is the significant increase in online shopping, particularly through social media platforms. Furthermore, those online purchases are becoming more prevalent on platforms supporting short-form video content such as TikTok, Instagram Reels, and Youtube Shorts. For example, consumers spent $3.8 billion on shopping through TikTok in 2023 (Ceci, 2025). Due to its emerging popularity, brands are allocating more resources to it. In 2024, TikTok ad revenue was $23 billion, a 42.8% increase from the previous year (Iqbal, 2025).

Short-form social media channels are different from other channels, so are branded ads. For example, a Facebook in-stream video can be 5 seconds to 10 minutes long (Meta, n.d.) and a Youtube video ideally is between 6 and 8 minutes long (Brafton, 2024). The length of video ads on those channels, therefore, has much flexibility. Meanwhile, for TikTok, the videos should be 3 minutes or shorter (Hayes, 2023). Branded ads thus are short as well. Also, it is typical for brands to use a sales approach in their advertisements on regular social media platforms like Facebook or Youtube. Yet, using a sales approach on short-form channels hurts consumer engagement (Xiao et al., 2023). Brands thus have to adjust their ad design when using these channels.

Among many differences between short-form and regular social media channels, the presence of trending content notably changes the way brands create their ads. For news feeds on Facebook, with a few exceptions such as the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, new posts distinctively vary across individuals. Meanwhile, for short-form videos, consumers may apply certain trending sounds, dance moves, augmented reality effects/filters, or recording styles to their videos. The videos using the same trends may sound and/or look similar to each other, with each user adding their own twist. Since these trends are well received, brands also adopt this strategy for their ads. For example, following the POV (point of view) trend, a person will share a point of view that reflects a certain character or situation, such as the POV of a new professor starting his/her career (Open Influence, 2023). This POV is presented as a short text on the top of the video with the content of the video illustrating it. As of 2023, more than 700 billion videos were created using this trend on TikTok. This same trend is also viral on Instagram with 3.5 million posts using the hashtag #pov. Brands also utilized this trend. An example is Cross Angel, a clothing brand, who made a POV video showing that the whole school wears their brand. The brand had a great success with 7 million views and nearly 1 million likes (Figure 1). As Wang (2021) suggests, interactive marketing can be fun and exciting, which encourages consumer engagement. The use of trending content elements in short form ads is a perfect example of this aspect of interactive marketing. Whereas trending content sounds positive for ad performance, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no empirical research examining the effectiveness of this strategy.

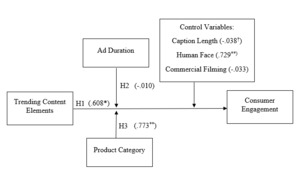

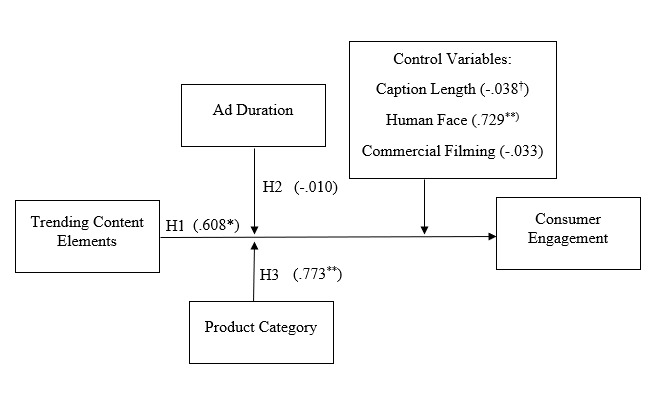

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the impact of trending elements in branded ads on consumer engagement with those ads. To do so, we did a content analysis of 750 short-form ads. Our findings show a positive effect of trends on consumer engagement as reflected by the number of likes, comments, and shares. Further analysis indicates that this effect significantly depends on product categories (i.e., services versus goods). The effect, however, does not vary with the duration of the ads. The results are also robust when controlling for caption length, the presence of human faces in the ads, as well as the recording styles of the ads. In addition, the study shows that certain control factors like human faces and caption length can affect ad effectiveness whereas others do not.

The paper has four important implications for marketing literature and practitioners. First, the present paper is the first to introduce and study trending elements in short-form video advertising, where users can add their own twist, as a distinct form of virality. Prior research has conceptualized virality as identical content that is repeatedly disseminated across users (Reichstein & Brusch, 2019), with limited attention to the value users or brands can add before sharing (Schulze et al., 2014). In contrast, short-form platforms enable variation in which users and brands can use popular video formats, filters, and sound effects and add a twist tailoring toward their own audience. These trending elements allow for both personalization and product integration, offering opportunities that previous viral challenges (e.g., the Ice Bucket Challenge) could not fully support. By examining the role of trending elements in advertising effectiveness, our study provides a new perspective on virality by shifting the focus from simple replication of content to the strategic use of customizable viral components that benefit both users and brands.

Second, the study advances understanding of product category effects by directly comparing consumer engagement with short-form advertising for physical goods and services. Prior research has generally examined either goods or services in isolation. For example, Xiao et al. (2023) showed that experience goods (e.g., cosmetics, liquor) had more consumer engagement than search goods (e.g., furniture, sporting equipment). Meanwhile, Shahbaznezhad et al. (2021) focused on airline industry while examining customers’ social media engagement. There has been little effort to systematically compare goods and services within the same framework. By incorporating both categories into our analysis, our findings show that product type, particularly the distinction between goods and services, plays a critical role in shaping consumer engagement with short-form ads. The paper also responds to the call from Barger et al. (2016) who suggest that future research investigate the relation between consumer engagement and product/service offerings.

Third, this study contributes by identifying underexplored creative elements, the presence of human faces and the length of captions, as significant drivers of consumer engagement with short-form ads. Whereas prior research has focused on factors such as emotional content (Araujo et al., 2022) and sound features (Lu & Shen, 2023), little attention has been given to these visual and textual cues, even though they play an important role in shaping consumer responses.

Finally, this study contributes by empirically testing consumer engagement with a substantial sample of real branded advertisements on short-form platforms, rather than relying on brand-generated videos or survey-based proxies. Prior research has often examined videos posted from brand accounts that may be designed to entertain rather than promote products (Akbari et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2023) or has relied on consumer perceptions collected through surveys (e.g., Ananda & Halim, 2022; Han & Zhang, 2020). In contrast, our focus on paid advertisements provides insights into how consumers respond to true promotional content. Given that audiences are often more alert to and hold negative attitudes toward paid advertising (Cho & Cheon, 2004), studying actual branded ads offers a more realistic and challenging test of advertising effectiveness. This contribution not only advances theoretical understanding of short-form advertising but also highlights the need for future research to further investigate real paid ads to provide advertisers with practical guidance for campaign design.

Literature Review

Consumer engagement and social media

Consumer engagement refers to “a multidimensional concept comprising cognitive, emotional, and/ or behavioral dimensions, and plays a central role in the process of relational exchange where other relational concepts are engagement antecedents and/or consequences in iterative engagement processes within the brand community (Brodie et al., 2013, p. 107).” Over the years, researchers have applied multiple approaches to understand consumer engagement. A few researchers identify consumer engagement as a unidimensional construct (Sprott et al., 2009), while others propose a multidimensional view where the consumer engagement construct is composed of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions (Brodie et al., 2011; Vivek et al., 2012). Particularly, consumer engagement is conceptualized as a psychological state characterized by dynamic interactive engagement processes that are context dependent (Brodie et al., 2013).

In the context of social media, consumer engagement refers to a set of measurable actions of consumers on social media in response to the social media context (Barger et al., 2016). These actions include reacting to a content post (e.g. likes and hearts), posting comments on the content (e.g. Tik Tok comments, Instagram comments), sharing content with others (e.g. share Instagram stories, reels), and post user-generated content (UGC) (e.g. product reviews, Instagram and TikTok posts) (Barger et al., 2016). Thus, engagement on social media centers on consumers’ actions to follow, like, share, subscribe, and comment (Cao et al., 2021). Advancing our understanding of consumer actions, prior research has examined engagement behavior from the perspective of consumption, contribution, and creation of content (Cao et al., 2021). As per Cao et al. (2021), consumption constitutes minimum engagement, where consumers passively consume social media content. Examples include reading a blog and watching a video posted by an influencer. Contribution represents a higher amount of engagement, entailing interactions with the brand and peers (e.g., commenting on a post or sharing a post among peers). Lastly, creation represents the highest engagement level, where consumers generate the content and post it on social media. Examples include posting a product review video or posting a picture with a specific brand.

Over the years, extant research has provided rich insights into consumer engagement. For example, in the context of brands on social TV, hedonic brands compared to utilitarian brands evoke higher intention to engage and engender positive electronic word of mouth (eWOM) (Sen et al., 2025). A meta-analysis by Blut et al. (2023) suggests that cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of consumer engagement result in positive marketing outcomes contingent upon the platform’s interaction intensity, richness, type, and the initiation of the interaction. Thus, consumer engagement differs from platform to platform. For example, Unnava and Aravindaskhan (2021) found that posts on Instagram sustain longer than on Facebook and Instagram. Further, prior research shows that consumers’ consumption, contribution, and creation behaviors are positively affected when the social media platform is richer than leaner, and the content is trustworthy (Simon & Tossan, 2018). The nature of the posts also influences consumer engagement. Pezzuti and Leonhardt (2023) found when brands’ messages included negations, they appeared powerful and thus, consumers showed higher likelihood of engaging, as they are generally more inclined towards powerful brands. In the context of stories posted on social media, the story plot, characters, and verisimilitude activate each of the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). Particularly, the story plot elicits cognition-based engagement, the characters evoke emotional transfer from the story to the viewers, and perceived verisimilitude translates into cognitive and behavioral reactions, underlining the interactive nature of consumer engagement. To that end, consumers can be both the subjects of engagement and the objects of others’ engagement (Dessart & Pitardi, 2019). Overall, previous research provides concurring support suggesting that engaged consumers show higher consumer loyalty, connection, trust, commitment, emotional bonding, and empowerment (Brodie et al., 2013).

Factors driving consumer engagement with ads on short-form social media

As a result of the rise in popularity of social media platforms like TikTok, there has been a sharp increase in the amount of research put into short-form video advertisements on social media platforms (e.g., Araujo et al., 2022; W. Li et al., 2022; Wahid et al., 2023). These studies have used a variety of different independent variables to answer their research questions. Short-form video advertisements have a specific set of factors that set them apart from other social media advertisements and change the way that they perform. Most research addresses the question, “What characteristics make these advertisements successful?” We looked at various independent variables to assist us with our research.

One popular independent variable used to study the success of short-form video advertisements is the genre of the content. Araujo et al. (2022) use emotional content as a genre to gauge how it affects consumers’ purchase intention. Emotional content in ads helps create a relationship between the brand and the consumer, making the consumer feel more passionate about the contents of the ad. The authors thus found that when advertisements on social media invoked a positive emotional response, they were shared more. This phenomenon was heightened with “Generation Z” consumers as they found that these positive emotions are the ones that they want to talk about and therefore will share the ad and talk more about it.

Additionally, ad duration has been studied as a determinant of short-form video ad effectiveness. Holmes (2021) claimed that there has been a lot of research done on the effect of ad duration; however, the majority of this research had been done on traditional television ads. Those studies concluded that the longer the television ad was, the better consumers’ recall was because the ad tended to repeat information. Filling the gap by studying the possible effect of ad duration on social media platforms, Holmes (2021) concluded that consumers had significantly better recall and recognition with 30 seconds ads than they did with 15 second ads. Li et al. (2022) also looked into ad duration for short-form social media ads. They posit that because a shorter ad reduces the amount of time that the consumers have to spend watching it, it would improve their experience on the short video platform. Li et al. (2022) deduced that brands should try to make ads as short as they can because the shorter ads contributed to a more positive experience on the platform, making the ads more effective due to positive ad attitudes.

Furthermore, previous research examines sound factors of the ads. Wahid et al. (2023) looked at if the ad using a cover sound or the original video’s sound had an impact on ad effectiveness. Using the ideas of Media Richness Theory, they classified cover sounds as more “rich” and original sounds as less “rich” to see if this theory could be applied to short form video ads. The author however did not find a significant difference in customer engagement between these two sound categories. Similarly, Lu and Shen (2023) also looked at the impact of sound factors on ad effectiveness. However, they aimed to access and analyze hidden features of these ads. They looked into specific acoustic features of the ads’ sound rather than if it was a cover or an original. Lu and Shen (2023) concluded that the sound factors they picked (zero-crossing rate, spectral centroid, etc.) also had no significant effect on user engagement.

In short, prior research has looked at how content genre, ad duration, and sound factors affect consumer engagement. “Trends” on short form video platforms are ideas for videos that become very popular across the app. Many people will participate in the trend by using the same sound, doing the same dance, or using the general template for the video that the trend uses. Short form video advertisements on social media apps have a special opportunity to be able to participate in trends and gain attention from consumers. In-stream and television ads do not offer such an opportunity. Our research therefore seeks to identify the potential benefit of trending content for advertisers by measuring the impact of such content on ad effectiveness.

Consumer engagement as a determinant of consumer decisions

Prior research on short-form video advertising has shown that consumers’ engagement with the ad is a positive predictor of their decisions (e.g., Ge et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2023). Consumer engagement refers to the level of involvement, interaction, and emotional connection that consumers have with a brand, product, or marketing content. It goes beyond passive observation and involves active participation, attention, and response from consumers. Engaged consumers are more likely to be loyal, advocate for the brand, and have a deeper connection with the company (Xiao et al., 2023). Vander Schee et al. (2020) further show that online consumer engagement can lead to other important brand outcomes such as brand attitude, disposition, and affirmation connection. Accordingly, Han and Zhang (2020) find that the more users interacted with the ad, the better their attitudes were toward the ad and the brand itself, therefore making the ad more effective. Similarly, Ge et al. (2021) find that user engagement of short-form ads positively drives product sales. Given the importance of consumer engagement as a reflection of an ad’s performance, we examine the effect of trending content, along with other control variables, on this metric as the main dependent variable.

Hypotheses

Trending content elements and consumer engagement

We draw on the halo effect to explain the influence of trending elements on consumer engagement. The halo effect theory suggests that consumers tend to have a cognitive bias which influences their attitude and behavior (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). Particularly, the global evaluation of an object influences the evaluations of individual attributes of that object. As an example, if a person appears to be nice, other people will likely believe they have nice attributes. Specifically, in a longitudinal study Nicolau et al. (2020) found that the ratings of a travel location varied substantially and were influenced by other attributes such as value for money, staff, and cleanliness. Thus, halo effect causes spillover among attributes other than the focal attribute (Nicolau et al., 2020).

In the digital marketing context, Minge and Thüring (2018) showed that when individuals interact with a mobile digital audio player, their initial impression of the visual aesthetics of the device positively influences the perceived usability of the device. However, recent research found that the halo effect goes beyond the perceived usability of the device and influences the content watched on the device. Specifically, Stewart and Perren (2023) demonstrated that dependence on a smartphone creates a halo of trust which enhances trust in the mobile device and in turn translates into increased trust in the advertising viewed on the device and increased purchase intentions. Likewise, considering the context of our research, trending elements are those that are popular and widely shared. Previous research has shown that viral content is often positive for two reasons (Berger & Milkman, 2012). First, from the sender’s standpoint, consumers prefer to share content that presents them in a favorable light and makes others feel upbeat. Second, from the receiver’s perspective, positive content shared by others can enhance mood and foster social connection. Accordingly, trending elements frequently arouse positive emotions and attitudes, which helps explain their popularity and virality. When an ad includes trending elements, consumers’ positive attitude toward the trending elements will transfer to their reactions to the ad, thereby enhancing engagement with the ad. Consistent with this logic, the algorithms of short-form channels also push the video content using the same trends to their users. In other words, if a user interacts with a video following a certain trend, such as the POV one, he/she will likely see other POV videos. As another example, if a user is interested in a dance move with a specific sound, the algorithms will show videos of other users that have the same move and sound.

Research suggests that appropriate combinations of common themes, music genres, and sentiment can strengthen the involvement and awareness of short-form video entertainment (Zhang et al., 2022). The combinations of themes and music could create a bias in the form of a halo effect which could evoke a favorable response in users even if the performance of the featured offering is unsatisfactory (Thorndike, 1920). We reason that the presence of trending elements in short-form video ads will create a halo effect which in turn will yield favorable responses from consumers, thereby increasing consumer engagement. Our reasoning is in line with Xiao et al. (2023), who found that entertainment in the short form videos on TikTok have significant impact on consumer engagement. Accordingly, we expect that the presence of trending content elements in short-form ads will make the ads more engaging. Thus, we hypothesize,

H1: The presence (vs. absence) of trending elements in short-form advertisements will lead to higher (vs. lower) consumer engagement.

Moderating effect of ad duration

Over the years, most of the research on ad duration has focused on television advertisements (Singh & Cole, 1993). Specifically, research on television ad durations has investigated the length of ads on ad recall, brand identification, and ad related information (Batra & Ray, 1986; Mord & Gilson, 1985; Newstead & Romaniuk, 2009; Patzer, 1991; Singh & Cole, 1993). While Gaines (2020) showed that 15 seconds television advertisements were more effective than 30 second ads due to their focused messaging and targeting, a substantial portion of research has found longer ads to be more productive. Specifically, longer ads compared to shorter ads are found to be more effective as they provide more information, allow more processing time, and repeat the information multiple times in the advertisement (Batra & Ray, 1986; Singh & Cole, 1993). Particularly, 30 second ads were more effective in generating ad recall than 15 second advertisements (Mord & Gilson, 1985; Newstead & Romaniuk, 2009; Patzer, 1991; Singh & Cole, 1993).

Whereas longer ads can provide more information than shorter ads, they may weaken the spillover effect of trends on ad engagement. According to Zillman (1971), the arousal from one stimulus spills over to another when the cognitive closure between the two stimuli causes a loss of awareness of arousal from the initial stimulus. In other words, the spillover effect from a popular trend to the ad utilizing it occurs if consumers cannot distinguish which portion of the excitation is from the trend, as the trend blends together with the brand and its ad (S. Li et al., 2023). However, with longer ads, the emotional “spillover” has more time to dilute or even be disrupted by other factors, such as storytelling that does not align perfectly with the trend. The positive emotions from the trend, such as humor and excitation, will diminish accordingly. We, therefore, expect that shorter TikTok ads with trending elements will yield higher consumer engagement compared to longer Tik Tok ads.

H2: The impact of trending elements on consumer engagement will be greater for shorter ads than for longer ads.

Moderating effect of product category

Unlike tangible goods, services are interactive in nature at their core (Brodie et al., 2011; Hollebeek et al., 2014). As a result, the advertising strategy for goods differs from that for services (Abernethy & Butler, 1992). We, therefore, anticipate different dynamics of how the trending elements of short video advertisements would interact with goods versus services (Behnam et al., 2021). Specifically, we expect that the effect of trending elements of short video advertisements on consumer engagement will be more pronounced for goods than for services.

Previous research pertaining to the effect of goods and services on consumer engagement has shown that consumer engagement is stronger in services context compared to goods (Behnam et al., 2021; Kumar & Pansari, 2016). For example, Leek (2019) found that tweets from a service company led to more behavioral engagement than tweets from product companies (Leek et al., 2019). Behnam et al. (2021), in the context of sports, showed that the effect of customer learning and customer knowledge sharing on consumer engagement was stronger in services rather than goods context. In contrast to tangible goods, services are intangible, simultaneously produced and consumed, and inseparable (Brodie et al., 2011; Grönroos, 2001), and as a consequence, consumers are likely to seek more information and interact more intensely with service offerings, thereby exhibiting more engagement behaviors (Fernandes & Castro, 2020). For example, research on brand communities suggests that members perceive service brand communities as a suitable avenue to raise and discuss problems, and share their reactions through comments with the brand and users (Fernandes & Castro, 2020).

Although previous research shows that services yield stronger consumer engagement, the research was mainly in the context of social media brand communities (Fernandes & Castro, 2020), sports (Behnam et al., 2021), tangibility and product involvement (Żyminkowska et al., 2023), and Facebook brand pages (De Vries & Carlson, 2014). While research provides rich insights, it ignores contexts where consumers are interested in spontaneity and are looking for stimuli that are highly interactive and congruent with their prevailing state. Particularly with TikTok, where consumers are looking for short-term immediately accessible content, consumers would be less inclined to process the complexity of messages associated with the intangibility of services. Research shows that consumers under high construal draw on intangible attributes in their service evaluation, whereas consumers under low construal rely more on tangible features (Ding & Keh, 2017). Thus, the evaluation of tangible and intangible features differs. In the context of social media platforms, Pittman and Li (2025), examined the differences between consumers’ interactivity on Instagram and TikTok, and found that low construal sustainability messages were more appropriate for TikTok, while high construal messages were suitable for Instagram. This is because TikTok’s fast-paced highly interactive video snippets and dynamic user-generated content, are more aligned with the processing fluency in low-construal messages, which emphasize immediate, concrete details and actions. We reason that, relative to services, users would engage more with the content featuring goods as they would be less invested in interpreting the complexity associated with services. We, therefore, anticipate that in the context of short form video ads on TikTok, the trending elements will exert a stronger effect on user engagement for goods than for services. Thus,

H3: The impact of trending elements on user engagement will be greater for goods than for services.

Methodology

Data collection

We collected ads from the creative center that TikTok developed for businesses. In this center, business accounts can access top performing ads from various industries around the world. During a three-month period (September – November 2022), two students who used TikTok daily and thus were familiar with the platform collected 750 ads in total – 125 ads from each of the six different products for two categories: real estate and home rentals, financial services, and higher education for services; and women’s clothing, men’s clothing, and pet products for physical goods. To control for the potential effects of cultures and consider the students’ familiarity with the content for American users, we focused on the ads promoted in the United States.

While collecting each ad, the students extracted information including the duration of the video, the caption, and the number of likes, comments, and shares. Furthermore, they coded the ad based on 1) the presence of human face, 2) the use of trending elements, and 3) the professional appearance of the ad. In this study, we define trending content elements as recurring creative features, such as sounds, on-screen text, or recording styles, that are widely adopted and reproduced by multiple users within a platform, thereby gaining collective visibility and recognition as part of a viral trend. Operationally, we coded an element as “trending” when it (a) appeared in multiple videos from different users beyond the focal ad, and (b) was recognizable as part of a broader trend (e.g., a specific soundtrack, dance move, or POV framing). To ensure accuracy, student coders marked “yes” when identifying such elements that they repeatedly saw before and provided a brief descriptive note of the trend. These descriptions were used as a quality-control step to verify that the classification was both consistent and aligned with our definition of trending content elements. Importantly, we distinguished trending elements from general ad features (e.g., music, text, recording style) by requiring evidence that the feature was not unique to the focal ad but circulated across the platform as part of a recognizable trend.

Descriptive Analysis

Overall, for our sample, the average duration of the ads was 24.21 seconds long. The shortest ad in our sample was 5 seconds long and the longest one was 61 seconds long. The average duration for all of the service ads was 25.29 seconds long. The average duration for all of the ads for physical goods was shorter - 23.17 seconds long. The average duration of the ads that feature trends was 24.8 seconds long. Without trends, the ads were slightly shorter – 23.78 seconds. It does not appear that there was much variance in the average duration of the ads among the product type or the trend condition. There were 333 ads that utilized a trending content element, which was 44.4% of the sample size. Analyzing the trends in those ads, we found that using popular audio and filter effects was the most popular one (140 ads), followed by on-screen text & emojis (70 ads) (Table 1). Notably, the number of ads that had a human face was relatively high, which was 70% (529/750) of the sample size. Meanwhile, the percentage of ads that were commercially filmed was low 43.6% (327/750), compared to those filmed casually. The caption length was low with 8.64 words on average, and no words as the lowest and 20 words as the highest.

Main Analysis

We ran an ordinary least square (OLS) regression analysis with consumer engagement as the dependent variable. Consumer engagement was measured by the number of likes, comments, and shares. Due to the significant differences in engagement between posts (e.g., 0 like versus 10,000 likes), we used the logarithm of the sum of these three engagement behaviors. Trending content elements, product categories, duration, and the interactions between trending content elements and the other two variables are the main independent variables. The caption length, the presence of human face, and whether the video was commercially filmed were included as control factors. The model formula is presented below.

\[\begin{align} Consumer\ Engagement &= \alpha + \ \beta_{1}Trend + \beta_{2}Product\ Category \\&\quad+ \beta_{3}Duration + \ \beta_{4}Trend \\&\quad*Product\ Category + \beta_{5}Trend*Duration \\&\quad+ \beta_{6}Caption\ Length + \ \ \beta_{7}Face\ Presence \\&\quad+ \ \beta_{8}Commercially\ Filmed + \ \varepsilon \end{align}\]

Table 1 shows the regression results in Models 1, 2, 3 with likes, comments, and shares as the dependent variables, respectively. Model 4 presents the results for total engagement. All of these models had VIF numbers lower than 5, which satisfied the threshold for potential multicollinearity issues (Akinwande et al., 2015). As shown in Model 4, trending content elements had a strong positive effect on consumer engagement (B = .61, p = .03). Therefore, H1, which proposed the positive impact of trending content elements on consumer engagement, was supported. The results also showed that consumer engagement for services was higher than it was for physical goods (B = .77, p = .002). Meanwhile, ad duration did not have an impact on consumer engagement (B = -.01, p = .27). Furthermore, the interaction between trending elements and ad duration was also insignificant (B = -.005, p = .71). Accordingly, H2, which stated that the effect of trending elements would be stronger for shorter ads, was not supported. In contrast, we found a significant interaction between trending elements and product category (B = -1.01, p = .009). The effect of trending elements was weaker for services than it was for physical goods, supporting H3.

Regarding control variables, caption length had a negative effect on user engagement, but the effect was marginal (B = -.04, p = .06). Our results further showed that the presence of human face was significantly important (B = .74, p < .0001). It was a strong factor driving consumer engagement. Notably, consumers did not consider the format of the ads. Whether the ads were commercially filmed or casually recorded did not affect their engagement (B = -.03, p < .86).

General Discussion

The study shows that using trendy content elements in short-form ads can lead to greater consumer engagement. Furthermore, the effect is stronger for physical goods than it is for services. Meanwhile, ad duration has no impact on consumer engagement either through its direct effect or its interaction with trends. This finding suggests that consumers care more about the content of the videos and they may be willing to watch longer videos if these videos are interesting to them. The results however appear to be inconsistent with Li (2022) who proposes theoretically that firms should make their ads as short as possible on short-form social media channels. Furthermore, Xiao et al. (2023) found inconsistent effect of ad duration on engagement, whereas its effect was significantly positive for likes, positive for shares, and insignificant for comments. It is possible that our sample included real ads which tend to be short. Future research can further explore the situational factors that drive the effect of ad duration. Our results also show that the presence of human face is important since it positively affects engagement. In short form social media channels, firms do not need to film the ad professionally and commercially, which can be costly. The study shows that there is no difference in consumer engagement between ads causally created and those commercially filmed.

Academic and managerial implications

Current research contributes to interactive marketing literature by examining the effect of trending elements in short form video advertisements on consumer engagement. Previous research on the effect of short form video advertising on consumer engagement has focused on ad features such as performance expectancy, entertainment, tie strength, and sales approach and type of offerings, namely product or services (Xiao et al., 2023). While earlier research identifies entertainment as a key factor influencing consumer engagement, research provides insufficient evidence of what form of entertainment is most effective and for which types of offerings. Our work addresses this research gap by delving deeper into the entertainment feature and examining the effect of trending elements on consumer engagement. Specifically, we found that the presence of trending elements in short form video advertisements has a positive influence on consumer engagement, and that this effect is more pronounced for service offerings compared to product offerings. Thus, our proposed framework complements existing research on short form video advertisements and consumer engagement.

Prior studies also call for research on the interactive features of social media on consumer engagement (Wang, 2021). The present paper answers to this call by linking short-form social media platforms’ interactive features to consumer engagement through the examination of trending content elements in ads. Trends can easily be created on short-form social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram because of their interactive features like filters, voices, and sounds. Our findings show that these features and the trends created from them not only help consumers create content but also allow brands to connect with its customers with more personable ad content. Furthermore, in their systematic review paper, Barger et al. (2016) propose that the characteristics and norms of the social media platform can influence consumer engagement. The present paper provides empirical evidence for this factor. Trends represent one of the norms of the platform. Certain trends are popular on TikTok and Instagram but not on other platforms. Following trends on those platforms is a way for brands to show their interest and commitment to the community.

Further, previous work has investigated halo effect in multiple contexts such as smartphone dependence (Stewart & Perren, 2023), customer loyalty (Byun et al., 2020), stages of user experience (Minge & Thüring, 2018), tourism (Nicolau et al., 2020), brands (Leuthesser et al., 1995) and retail (Wu & Petroshius, 1987). While past research enriches our understanding of halo effects, research lacks explanation of when social media advertising could be subject to halo effects. In our work, we show that the effect of trending elements on consumer engagement is driven by the halo created by the short form of video advertising. This halo effect then translates into consumer engagement on social media. Thus, our work adds to the line of research by examining the halo effect in a novel context of short form video advertising on social media. In addition, we show that the halo effect of trending elements exists for service offerings but not for product offerings. Understanding of this effect complements work on services marketing and consumer engagement, by showing the differential effect of trending elements of social media on consumer engagement (Brodie et al., 2011; Grönroos, 2001).

Further, we found no significant main effect or interaction effect of ad duration and trending elements on consumer engagement. We reason that this non-significant effect could be because the nature of short form video advertisements being so short that the ad duration is inconsequential to consumer engagement. While previous research on television advertisements and digital advertising has majorly shown longer ads to be more effective than their shorter counterparts (Batra & Ray, 1986; H. Li & Lo, 2015; Moore et al., 1986), our results demonstrate that the ad duration is inconsequential for short form video advertisements on social media. However, we encourage future research in this area wherein researchers could vary the type of trending elements and ad duration and examine the consumer engagement associated with the ads.

The findings of our research have strong managerial implications. First, our results showed that the presence of trending elements had a significant impact on consumer engagement in short video advertisements format. Marketers can apply the findings and develop advertisements on social media platforms such as TikTok to enhance consumer engagement. Further, we found that the halo effect of the trending elements plays a key role in influencing consumer engagement. Research shows that the halo effect is more pronounced in the initial phases of consumer interaction with the offering (Minge & Thüring, 2018). Thus, using the short video ads in the early phases of marketing may help in enhancing the awareness of the offering. However, we suggest marketers have a clear knowledge of the target audience such that trending elements resonate the maximum. For example, an offering targeted at individuals in the age range of 30 to 35 years, may not identify with the trending elements that show individuals in the age range of 20 to 25 years. In addition, given the global nature of social media users, marketers could first gain a thorough understanding of the cultures and then tailor the trending elements to enhance the effectiveness of the short video advertisements. For example, brands can incorporate trending elements such as music of a particular culture, and then develop advertisements accordingly. Future research examining the effect of congruity of trending elements with the local versus global culture on consumer engagement could show interesting results.

Our research also showed the trending elements for service offerings yielded stronger consumer engagement, compared to product offerings. To that end, service companies could use our findings and leverage the short video advertisements format to communicate their message. Particularly, advertisers could use the short form video advertisements to mitigate perceived risks as research shows that consumers tend to gather more information about services (versus products) to minimize the perceived risks of using a service (George & Berry, 1981; Mortimer, 2002). While there was no interaction effect between trending elements and ads featuring products, we suggest that future research could examine the underlying factors that deter trending elements associated with product offerings to garner consumer engagement.

Limitations and future research

The present research has a few limitations. First, our research was specifically in the context of TikTok, which has a specific audience. Users of other short-form video advertisements such as snapchat, Instagram reels, etc. may have different characteristics. Thus, replicating this study and examining the effectiveness of the short-form videos on other platforms could be a rich topic of future research. We collected ads from the TikTok Creative Center, which provides access to ads that are not typically shared on businesses’ accounts and allows researchers to gather multiple ads within specific product categories. However, the platform prioritizes ads with stronger performance, which may introduce sampling bias. Accordingly, we suggest that future research explore alternative approaches to studying short-form ads that capture a more representative sample of the overall ad population.

Second, considering the initial investigation of our work, our research was exploratory, wherein we used content analysis as a research methodology. Future research could incorporate experiments to determine the types of trending elements that have the most impact on consumer engagement. For example, research could investigate types of music and dance moves that lead to most and least consumer engagement. Although we did not find a significant effect of ad duration and trending elements on consumer engagement, future research could vary the types of trending elements and ad duration and examine the effect on consumer engagement. Results in our study showed a significant interaction effect of services and trending elements, however, future research could delve deeper into the types of services and determine the services that lead to most and least consumer engagement. We hope this work motivates research on the emerging trend of short form advertisements on social media platforms.

Furthermore, the coding of video ads was divided between two coders without overlap, which prevented the calculation of a formal interrater reliability statistic (e.g., Cohen’s kappa). While we implemented safeguards, such as requiring coders to provide descriptive notes of each identified trend to ensure accuracy and consistency, future research would benefit from having multiple coders evaluate the same set of ads or testing the same ads in an experiment setting to further strengthen the robustness of the findings.

While the explained variance of our regression model is relatively modest, it is common in social media advertising where engagement outcomes can be influenced by a wide range of external factors beyond the ad itself, such as platform algorithms, prior brand exposures, and individual differences (e.g., Rabbanee et al., 2020; Voorveld et al., 2018). Importantly, our main results remain statistically significant, suggesting that trending elements meaningfully contribute to engagement despite the complexity of the context. Future research could extend this work by incorporating more contextual variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of engagement drivers.

Finally, while trends can evoke positive emotions, not all consumers are fond of certain trends. It is likely that some consumers may not like certain trends. Such a negative feeling towards a trend may spill over to the ad using it. Future research should investigate situations where consumers dislike a trend and whether this has a negative impact on their attitude towards the brand and its advertisements.