Introduction

According to Statista (2024), the global advertising spending rose from $733 billion in 2023 to $792 billion in 2024 in U.S. dollars which shows an increase of eight percent as compared to a growth rate below three percent in the previous year. Companies spend this large amount of money to communicate information about the products/services to their actual and potential customers. Companies promote their products/services by using advertising appeals as a theme of their advertisements (Kotler et al., 1991). According to Kotler and Keller (2003), advertising appeals can be divided into emotional and rational appeals. Rational ad appeals provide a description of the attributes and features of a brand, whereas emotional ad appeals focus on the social, psychological, and/or symbolic elements of the brand (Kotler et al., 1991). Within these “themes,” an advertisement, with either rational or emotional appeal, uses a frame (gain or loss) to communicate the recommended message. The messages in advertisements can generally have a gain or a loss frame (Smith & Petty, 1996). For example, Crest toothpaste uses a gain-framed advertisement that states, Crest’s “at-home whitening treatment will make your smile 8 levels whiter in 7 days,” highlighting the benefits of using the brand. In contrast, Sensodyne toothpaste uses a loss-framed advertisement that warns customers through its tagline, “don’t let tooth sensitivity stop you from enjoying your favorite foods,” emphasizing what consumers might lose by not using the brand. A gain frame refers to designing the message in a way that highlights the benefits of using the brand. On the other hand, a loss frame involves designing the message in such a way that it focuses on the losses of not using the brand. An advertisement is meant to convey the message to consumers using these inherent characteristics of framing and appeals. While appeals are used to compose advertising, message frames are used as an execution technique (Tsai, 2007). In other words, appeal/theme and message frame are an intrinsic, inseparable, part of an advertisement.

Research in the past has shown that different types of appeals have different impact on consumers’ attitude toward an ad and the advertised brand (Akbari, 2015; Burton & Gupta, 2022; Cadet et al., 2017; Khan & Sindhu, 2015; Rawal & Saavedra Torres, 2017). In addition, the way a message is framed has also been shown to have an impact on consumers’ product attitudes (Buda & Zhang, 2000; Kim & Chen, 2025). More recent research has deepened this understanding by examining how framing interacts with emotional and rational appeals to influence persuasion outcomes (Carfora et al., 2021, 2022; Florence et al., 2022; Ort et al., 2023; Stadlthanner et al., 2022; Yousef et al., 2022). However, despite this knowledge, advertisers still face the practical challenge of determining which combinations of message frames and advertising appeals are most effective in influencing positive consumer responses. Understanding this relationship is a real-world concern for marketers who must design persuasive messages that resonate with their audiences. Therefore, the present study seeks to address this practical issue by examining how message framing interacts with advertising appeals to shape consumers’ attitudes toward the ad and the brand.

Specifically, this study investigates which frame of message (loss or gain) works best with which type of ad appeal (emotional or rational) to create positive attitudes toward the ad and the brand, thereby enhancing advertising effectiveness. The current research uses psychological reactance theory by Brehm (1966) and broaden-and-build (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001) to develop and test the study’s hypotheses. This work also builds upon recent meta-analytic evidence showing the nuanced effects of gain-loss frames in persuasive communication (Kim & Chen, 2025), situating the current study within a broader and evolving theoretical context.

Theoretical Foundation and Hypotheses Development

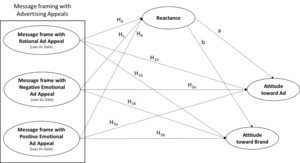

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model tested in this study. The model was developed by combining research from psychology (J. W. Brehm, 1966) with that from advertising (Reinhart et al., 2007; Stafford & Day, 1995). In line with recent theoretical developments, the current framework conceptualizes message frame (gain vs. loss) as a moderator that influences the strength and direction of the relationship between advertising appeal type (rational, positive emotional, negative emotional) and consumer responses (Carfora et al., 2021; Ort et al., 2023). The model implies that the impact of advertising appeals (rational and emotional) on consumers’ ad attitudes and brand attitudes depends on the frame of message (loss vs. gain) used in the advertisement. Further, the model shows that consumers’ reactance mediates the above relationship. These relationships are fully discussed in the following sections. While traditional models have positioned advertising as a persuasive force, Ehrenberg, Barnard, Kennedy and Bloom (2002) suggest that advertising primarily works by reinforcing and maintaining memory structures associated with a brand rather than directly changing attitudes or behavior. This view complements the current study, which examines how message framing and appeal types may shape consumers’ cognitive and emotional responses that contribute to long-term brand associations. In doing so, the present study extends prior work and differentiates itself from earlier investigations (including Rawal, 2019) by incorporating newer empirical insights and theoretical refinements on framing–appeal interactions.

Advertising appeals, Message frames, and Reactance

This study relies primarily on the reactance theory. Reactance theory (J. W. Brehm, 1966) concerns the psychological state of individuals when they are faced with a situation in which their freedom is threatened or restricted. Reactance is studied as a negative emotional/cognitive state (Dillard & Shen, 2005). In the context of promotion, threat to freedom may be induced by intense language (Miller et al., 2007), obvious intent to persuade against the behavior (Bensley & Wu, 1991), or a combination of these factors (Dillard & Shen, 2005). Intense language is characterized by the use of explicit messages directly communicating a source’s intent (Miller et al., 2007). It has been shown that hard sell tactics, which tend to be more explicit as compared to soft sell tactics, are less persuasive (Clee & Wicklund, 1980). Since the hard sell tactics reveal the intent of the persuader, they face greater resistance (S. S. Brehm & Brehm, 2013).

As a result of reactance, people often try to regain that threatened freedom by taking some actions (Clee & Wicklund, 1980) that will reduce the unpleasant feeling of reactance (S. S. Brehm & Brehm, 2013). When people are in a state of high psychological reactance in response to marketing communication, they can be more judgmental toward certain messages and can find those messages to be exaggerated or overstated (Shen et al., 2009). With the effect, psychological reactance can lead to reduction in persuasiveness of the message and/or it can also create a boomerang effect (Clee & Wicklund, 1980). This effect can lead to the desire to engage in the threatened behavior even more strongly or can alter their attitudes to being more positive toward the prohibited behavior so as to regain their threatened freedom (Wicklund, 1974).

Reactance has also provided explanation with respect to the effectiveness of message frames (gain versus loss) (Cho & Sands, 2011). Message framing is a persuasive technique to make the consumers comply with the message by focusing either on the benefits of complying or on the costs of not complying with the suggested behavior. Specifically, gain-framed messages highlight the positive outcomes to be experienced by complying with the advertiser’s recommendations (Rothman & Salovey, 1997). On the other hand, loss-framed messages emphasize the negative consequences to be experienced by not complying with the advertiser’s recommendations (Rothman & Salovey, 1997).

Psychological reactance has been shown to cancel out the effect of negativity bias, which is considered to be the underlying principle for the success of loss frame messages (Burton & Gupta, 2022; Shen, 2015). Loss frame messages overlap with the threat component of negative emotional appeals as these messages highlight negative consequences. According to Shen (2015) and Cadet et al. (2017), loss framed messages tend to develop psychological reactance because when negative consequences are highlighted in a message, consumers can feel that the behavior is being forced on them (Cho & Sands, 2011). In addition, since loss frame messages tend to induce negative emotions, the perceived forceful behavior can be felt as manipulative by the consumers (Witte, 1992). On the other hand, since gain frame messages do not attempt to restrict or threaten people’s freedom to act, these messages do not lead to reactance (Reinhart et al., 2007).

As suggested by this literature, inducing reactance is something that should be avoided in advertising and promotion messages. Broaden-and-build (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001) may be a theoretical foundation with implications of how to overcome the negative attitude and behavior associated with reactance in advertising. Broaden-and-build states that positive emotions have the potential to widen people’s temporary thought-action range. In other words, if consumers experience positive emotion, it can lead to an increase in their range of acceptable behavioral options (Kahn & Isen, 1993). This can further help build their long-lasting substantial and rational resources. According to the theory, positive emotions can expand people’s multitude of acceptable behaviors. Research has shown that people who experience positive emotions exhibit diverse and efficient arrangements of thought (Isen & Means, 1983). People’s preferences for various diversified behavioral interests have also been shown to have increased due to positive emotions (Cunningham, 1988; Kahn & Isen, 1993). In context of advertising with positive emotional appeal, consumers might find certain characteristics portrayed in the ad acceptable, which otherwise they would not have in absence of positive emotion.

According to Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, & Tugade (2000), negative emotions limit a person’s range to think and take action because they give rise to certain action likelihood, for example, attacking. However, positive emotions widen peoples’ thought-action range in such a way that makes them accept certain thinking and behavior that they would normally not accept (B. Fredrickson et al., 2000). Fredrickson et al. (2000) suggest that broadening positive emotions can also help in negative emotion regulation. They argue that if positive emotions widen a person’s range of thought and action, those positive emotions should also deliver adequate remedies for the continuing impact of negative emotions. They demonstrate in their study that positive emotions “correct” or “undo” the aftereffects of negative emotions. Thus, the following hypotheses are offered as a way to understand how the combination of message appeal and frame may create different effects on consumer attitudes towards advertisements and brands through the lens of reactance and broaden-and-build theory.

Rational Appeals and Gain vs Loss Framed Messages: Advertisements with rational appeals directly present the factual information that stimulate logical thinking and analysis about the advertised product or service (Rawal & Saavedra Torres, 2017; Stafford & Day, 1995). Ads with rational appeals are meant for consumers who base their purchasing behavior on logical and factual information (Burton & Gupta, 2022; Schiffman & Kanuk, 2004). Due to the fact that gain-framed messages emphasize the benefits of a behavior (Smith & Petty, 1996), using these messages may help in building a more favorable logical acceptance of the suggested behavior. Hence, using gain-framed messages for rational advertisement appeals is expected to contribute to a more positive consumer attitude toward the advertisement and subsequently toward the brand.

Contrary to the gain-framed messages, loss-framed messages focus on negative outcomes by showing the costs of not performing a particular behavior (Smith & Petty, 1996). Using these messages toward rational thinking consumers, who tend to base their decisions on logic, information, and facts (Schiffman & Kanuk, 2004), could potentially create a conflicting effect on their logical analysis. For example, if a rational advertisement emphasizes the losses of not purchasing a particular brand, some consumers might perceive the message as somewhat incongruent with their logical decision-making. This perception may lead to consumers feeling that the advertisement or brand is trying to influence their behavior, which could increase the likelihood of psychological reactance (Cho & Sands, 2011). Hence, the informativeness of rational appeals and the negativity of loss framed messages, together, would yield less positive attitudes toward advertisements and the advertised brands, as compared to gain framed messages. Based on the discussion above, the following are hypothesized:

H1a: Gain-framed messages with rational appeals will have a significantly more positive attitude toward the ad, as compared to loss-framed messages with rational appeals.

H1b: Gain-framed messages with rational appeals will have a significantly more positive attitude toward the brand, as compared to loss-framed messages with rational appeals.

Negative Emotional Appeals and Gain vs Loss Framed Messages: Past research has shown that using gain-framed messages can evoke less reactance than loss-frame messages (Reinhart et al., 2007). When a negative (e.g. sad) emotional advertisement provides consumers with the information on benefits of performing the intended behavior, it might develop a feeling of empathy toward the ad (Aaker & Williams, 1998; Burton & Gupta, 2022). Empathy refers to recognizing and experiencing the emotional internal state that a person is going through (Hoffman, 1984). Empathy in emotional advertisements is a way to entertain consumers by providing them with the experience (Vorderer et al., 2001). Empathy makes consumers feel as if they are experiencing those emotions themselves and are getting affected by the situation. This leads to consumers developing a positive attitude toward the ad and the advertised brand (Escalas & Stern, 2003).

Given that emotional advertisement appeals tend to activate emotions and feelings of consumers (Holbrook & Batra, 1987), using loss-framed messages in negatively valenced emotional advertisements may increase the likelihood of stronger negative emotions (Chang & Lee, 2009). This could contribute to feelings of guilt, shame, or fear in some consumers (Brennan & Binney, 2010; Shen & Dillard, 2007). These negative emotions might increase the potential for anger or disgust, which can contribute to psychological reactance among certain consumers (Cotte et al., 2005). Finally, once consumers get the feeling of reactance, their attitude toward the ad, as well as the brand, will be negative. Based on the above discussion, the following are hypothesized:

H2a: Loss-framed messages with negative emotional appeals will have a significantly more negative attitude toward the ad, as compared to gain-framed messages with negative emotional appeals.

H2b: Loss-framed messages with negative emotional appeals will have a significantly more negative attitude toward the brand, as compared to gain-framed messages with negative emotional appeals.

Positive Emotional Appeals and Gain vs Loss Framed Messages: As discussed earlier, emotional appeals do not really provide concrete information about a product, rather they produce feelings and create a situation affecting consumers’ attitudes and behaviors (Sun, 2014). Unlike advertisements with rational appeals, ads with emotional appeals impress those consumers who are more emotionally involved with a brand than those with an intellectual involvement (Leonidou & Leonidou, 2009). These advertisements are made in such a way that they are supposed to affect the consumers on some emotional level so as to create a connection with the situation portrayed in the ad.

Advertisements with positive emotional appeals tend to create favorable associations with the brand by making consumers feel positive about the product (Cadet et al., 2017; Panda et al., 2013). When positive emotional appeals are used in an advertisement, they can broaden consumers’ mindset and create favorable attitudes toward the ad and the brand (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001; Rawal & Saavedra Torres, 2017). These advertisements and brands work on positive feelings for effectiveness. Using gain frame messages for these positive feelings can help in producing more persuasion (Yan et al., 2012). Hence, positive emotional advertisements with gain framed messages can lead consumers to build positive attitudes toward the ad and the brand.

The negativity, created by loss-framed messages, has been shown to be linked with psychological reactance (Reinhart et al., 2007). Hence, an advertisement with loss-framed message would generally create reactance, leading to negative attitude formation. However, when an advertisement uses positive emotional appeal, according to broaden-and-build theory, the positive emotions of the advertisement may reduce or attenuate the effect of negatively-framed message (R. W. Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998). In other words, the positive emotional appeal could help moderate the influence of reactance in the advertisement, depending on the intensity of the emotions conveyed. This will lead to creation of positive (rather than negative) attitude formation toward the advertisement and brand. The overall effect would lead to consumers developing a positive attitude toward the ad and the brand due to the overall positivity created by the ad.

Interestingly, using loss frame messages for positive valence emotional ads can make the ad more distinguishing and informational than using gain frame messages (Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, 1990). Hence, emotional advertisements with positive appeals may partially offset the effect of reactance created by loss frames and could contribute to more favorable attitude formation compared to gain-framed messages under certain conditions. Hence, the following are hypothesized:

H3a: Loss-framed messages with positive emotional appeals will have a significantly more positive attitude toward the ad, as compared to gain-framed messages with positive emotional appeals.

H3b: Loss-framed messages with positive emotional appeals will have a significantly more positive attitude toward the brand, as compared to gain-framed messages with positive emotional appeals.

Reactance as a Mediator: Reactance leads to an intensified desire to accomplish the restricted behavior and simultaneously increases its perceived attractiveness (S. S. Brehm, 1981). Reactance occurs when a person feels that someone or something is taking away his or her choices or limiting the range of alternatives and manifests itself as a negative emotional state. In general, it can be said that an advertisement using loss-framed messages can signal to the consumers that their choice of taking a decision is being taken away by the advertiser/company. This would happen due to the negative language used in a loss-framed ad message (Xu, 2019). For example, an Allstate insurance commercial that warns ‘Mayhem is everywhere. Are you in good hands?’ illustrates a loss-framed message that can evoke reactance if consumers perceive it as fear-inducing or manipulative. Therefore, the baseline level for the mediation analysis is taken as gain-framed message. Even though it seems obvious that loss-framed messages should always lead to reactance, yet there can be some exceptions to this, based on the type of appeal used in the ad (Reynolds-Tylus, 2019). The following sub-sections discuss reactance, created by loss-framed messages, for each type of advertising appeal.

As discussed earlier, rational appeals help consumers analyze the product using logical reasoning based on products’ characteristics and features (Churchill & Peter, 1998). Rational appeals are supposed to develop logical thinking amongst consumers so that they can properly analyze the advertised product or service. Using a loss-framed message in an ad would mean telling the consumers what they will lose if they do not, for example, buy a particular product. But at the same time, these consumers know that the advertiser actually wants them to buy the product. In such case, the advertisement can face greater resistance because consumers might perceive these ads as overly intrusive or encroaching (Tucker, 2012). This can further threaten their freedom of choice and lead to reactance (S. S. Brehm & Brehm, 2013). Consumers with the feeling of reactance may develop negative attitude toward the information and the source of information. Hence, the following hypotheses are formed.

H4a: Reactance positively mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude toward ad.

H4b: Reactance positively mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude toward brand.

It has been shown that negative emotions develop the feeling of reactance and lead to change in attitude and behavior of consumers (O’Keefe & Jensen, 2008). Research also shows that negative emotions create threat to individuals’ freedom and thus relate negatively to the message effectiveness (Reinhart et al., 2007). These findings reinforce that negative emotional appeals are associated with the perceptions of freedom threat, leading to psychological reactance. Now using loss-framed messages, which are also associated with reactance arousal (Reinhart et al., 2007), for negative emotional advertisements would tend to double this impact and affect consumer attitudes. According to Clee and Wicklund (1980), negative emotional appeals can develop reactance amongst consumers, if they perceive the message to be manipulative. Now, using loss-framed message with negative emotional appeal can be perceived as manipulative. For example, when the Department of Health warns smokers that as few as 15 cigarettes can cause a cancerous tumor (loss frame message), then the manipulative wording of the ad, in combination with the appeal, can lead to reactance effects in consumers. Based on the above discussion, the following are hypothesized:

H5a: Reactance positively mediates the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward ad.

H5b: Reactance positively mediates the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward brand.

As discussed before, according to broaden-and-build theory (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001), positive emotions tend to widen an individual’s range of thoughts and actions. Therefore, positive emotional appeals used in an advertisement can broaden consumers’ mindset which can make them process ads differently. The positive emotions in an ad can “undo” the effects of reactance created by loss-framed messages (B. Fredrickson et al., 2000). It seems plausible that an advertisement with positive emotional appeal with a loss frame message can be accepted by the consumers because the positive appeal can broaden the consumers frame of mind and neutralize the negativity of the message frame. Hence, a message frame may not lead to reactance for positive emotional advertisements.

H6a: Reactance does not mediate the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward ad.

H6b: Reactance does not mediate the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward brand.

Research Design and Methodology

An experimental design was utilized to study the differences in effects of advertising appeals and frames. A 2 (Message frame: loss vs. gain) X 3 (Advertising appeals: rational, negative emotional, positive emotional) between-subjects factorial design was adopted for this study.

Pilot study

Prior to the main study, we conducted a pilot to develop effective manipulations for advertising appeals. T-test and ANOVA were conducted in this pretest to investigate whether the different print advertisements created for this study successfully elicited rational, negatively emotional, and positively emotional responses. The manipulation for advertising appeals was developed in a series of five pretests. Pretests 1- 4 were found to be ineffective in manipulating ad appeal. Each pretest was used to further refine the ads to be used in the main experiment.

Participants: 90 participants were recruited for the pretest using Mturk. We selected participants from the United States only, because the master qualification database helps in reducing threats to validity (Cheung et al., 2017). Participants were randomly exposed to one of the six conditions.

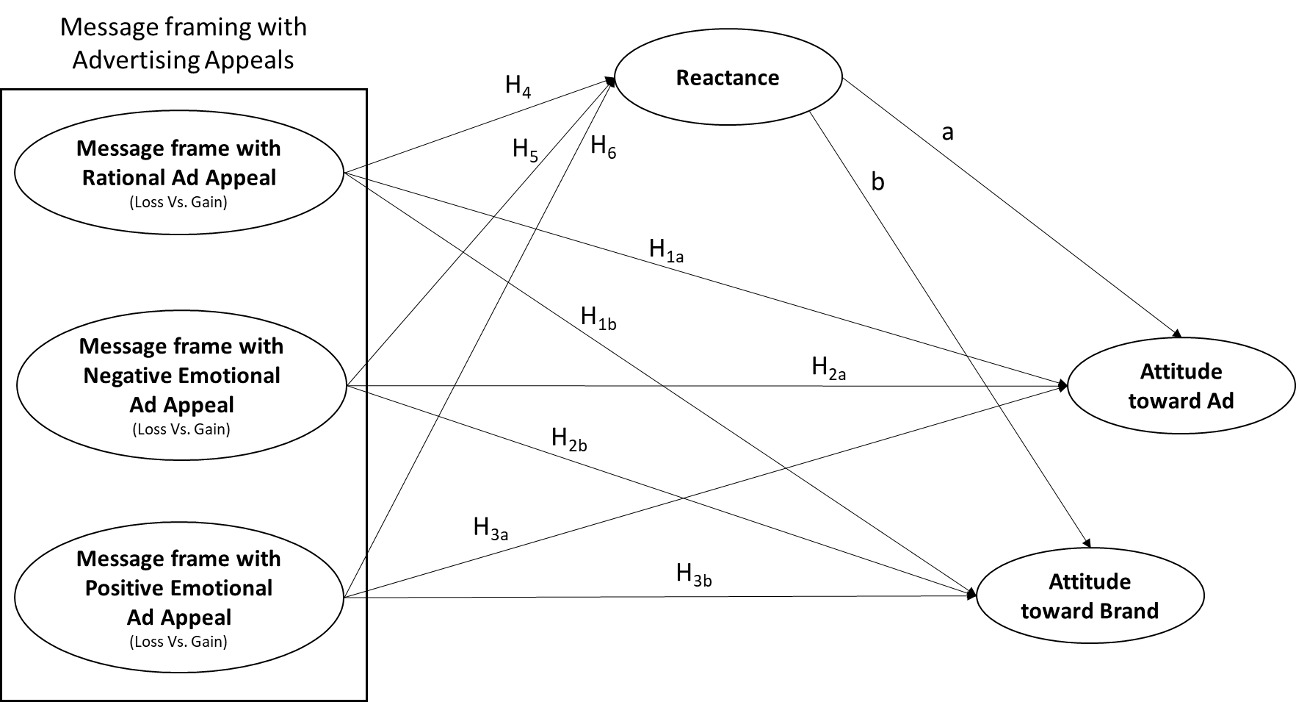

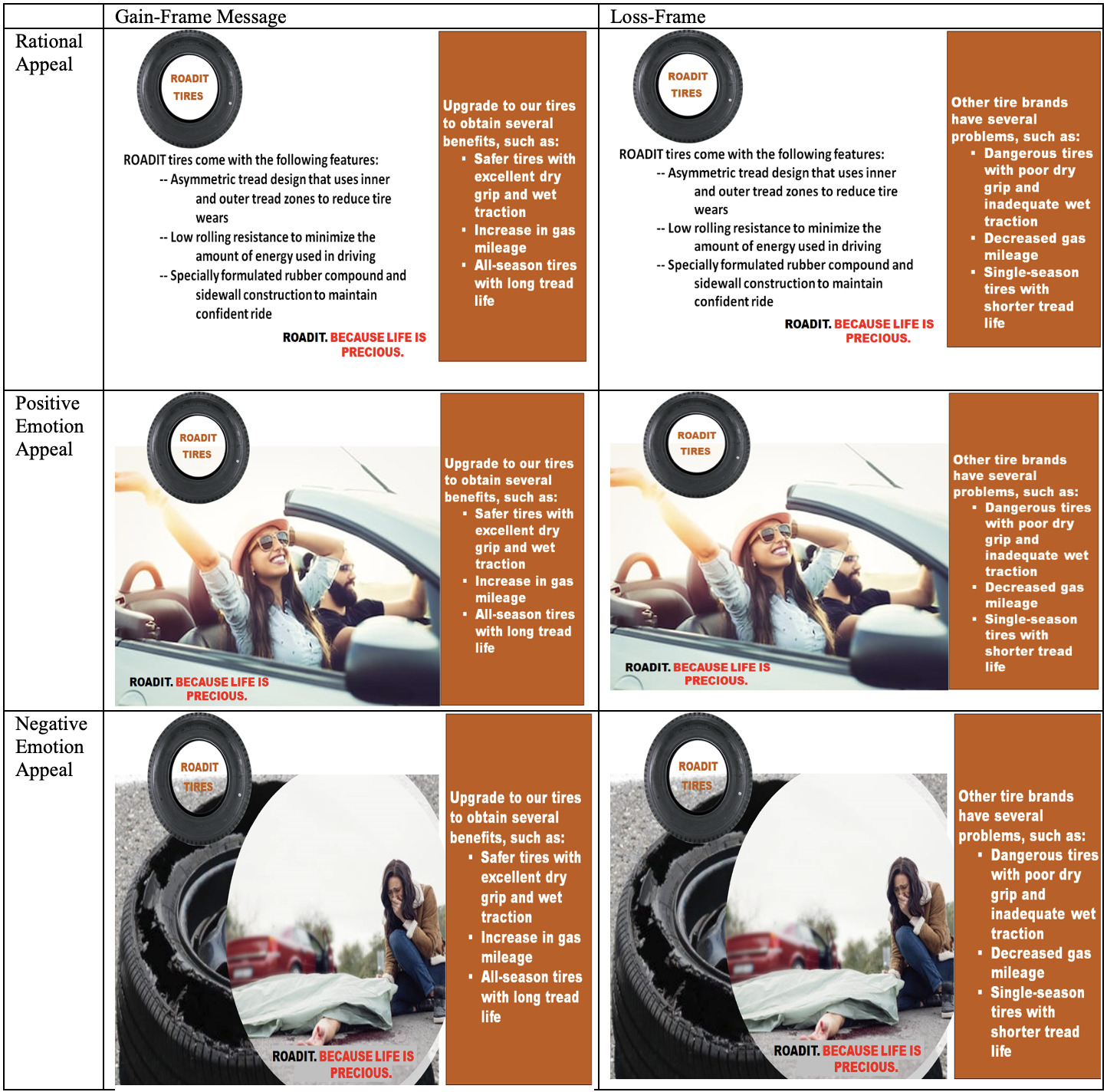

In addition, the pretest included manipulation checks for message frames to understand whether the messages in the ad were perceived as focusing on the benefits of using the current brand or the problems of using other brands. Manipulations for advertising appeals and message frames were conducted by showing the participants print ads for a fake tire brand named “Roadit”. The six print ads are shown in the appendix.

Study design and Stimulus: The pilot study was a 3 (ad appeal: rational, negative emotional, positive emotional) X 2 (message frame: gain, loss) experimental design. Participants were randomly exposed to one of the six conditions. Print ads for a fictitious tire brand named “Roadit” were designed specifically for this study. The ads were modelled after actual ads for a real tire brand. To elicit positive emotional ad appeal, we included a picture of a couple riding in a car with Roadit tires, smiling. To evoke negative emotional appeal, specifically sad, the ad included a picture of a lady mourning beside a body, with a busted tire in the background. The rational appeal conditions did not include photos. Rather, in place of the photo, the print ad provided technical information on the features and the associated benefits of the features of the Roadit brand of tires. The effectiveness of both the gain and loss framed messages were also assessed in the pilot study. Following previous research (Petrovici et al., 2019; Tsai, 2007; Yang & Mattila, 2020), the loss frame message emphasized the losses associated with choosing other brands while the gain frame message focused on the gains obtained if our brand is chosen. See appendix A for the print ads used in the study. After analyzing the ads, participants completed the items that were used as manipulation checks. Participants indicated their level of agreement/disagreement with the items and all items were 7-point Likert scales with 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree.

Manipulation Checks: Following Lee, Liu & Cheng (2018), we assessed the effectiveness of the ads used to manipulate message frames by asking participants to indicate their level agreement/disagreement with the statements “The ad stresses on the gains/benefits of using this brand of tires” and “The ad stresses on the losses/problems of using other brands of tires”. Independent samples t-tests revealed that participants felt the gain frame ads stressed more on gains/benefits of using the company’s tires (M=5.85, SD=1.25) compared to the loss frame ads (M=4.59, SD=1.98, p < .001). Further, respondents felt the loss frame ads stressed more on losses/drawbacks of using other company’s tires (M=5.84, SD=1.57) than the gain frame ads (M=3.83, SD=2.32, p < .001). Therefore, the manipulations appeared to have worked for message frames.

Based on the manipulation check process used by McKay-Nesbitt, Manchanda, Smith & Huhmann (2011), two items were used to assess the effectiveness of the manipulations for emotional ad appeal. They are “The ad made me happy” and “The ad made me sad”. The results indicate that participants felt the ad meant to elicit positive emotion did make them happier (M=4.34, SD=2.02) than the ad meant to elicit sadness (M=2.37, SD=1.87, p < .001). In addition, participants claimed that the sad condition made them sad (M=4.67, SD=2.11) more than the happy condition (M=2.52, SD=1.55, p < .001). Thus, the manipulations for emotional advertising appeals were effective. As a manipulation check for the manipulation of rational appeal, participants were asked to indicate the level of information provided in the ad on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represented the least and 10 represented the most information. A from one-way ANOVA indicated that participants felt that the rational appeal ad provided more information (M=6.97, SD=1.89) than both the positive emotional appeal (M=5.45, SD=2.53) and negative emotional appeal ads (M=5.10, SD=1.88, p < .05). There was no significant difference between positive and negative emotional appeal conditions (p = .80). Hence, the manipulations for rational advertising appeals appeared to be effective.

Main Study

Similar to the procedures used in the pretest, a 2 (Message frame: loss vs. gain) X 3 (Advertising appeals: rational, negative emotional, positive emotional) between-subjects factorial design was adopted for this study. Two hundred and nineteen MTurk participants were randomly exposed to one of the six conditions. The print ads used in the main study are the same as the ones that were used in the pretest. Similarly, we used the same items as those used in the pilot study to assess the manipulations. The manipulation check indicates that the print ads were effective since participants in the gain frame condition felt the ad stressed more on gains/benefits of using this brand of tires than (M gain =5.89, SD=1.25 vs M loss =4.02, SD=2.09, p < .001). Also, participants in the loss frame condition felt the ad stressed the losses/problems with not using the brand in question more than the gains of using it (M loss=6.10, SD=1.14 vs M gain=3.50, SD=2.08, p < .001).

Measures: Attitude toward ad was measured following Nan (2006): unpleasant/ pleasant, dislikable/ likable, boring/ interesting, and good/ bad (reverse coded) on a nine-point semantic differential scale. The measure for attitude toward brand was adapted from Spears and Singh (2004) (unappealing/ appealing, bad/ good, unpleasant/ pleasant, unfavorable/ favorable, and unlikable/ likable), but was changed from semantic to Likert type scale, anchored from strongly disagree to strongly agree, to create a difference between the two attitude scales (i.e. ad attitude and brand attitude). Seven-point Likert scale was used, an example of which is as follows: “The brand shown in the ad seems to be appealing.” Reactance was measured using scale items adapted from Dillard and Shen (2005). See table 1 for all the scale items and reliabilities.

We controlled for variables that although were not of direct significance, could impact the constructs under study. Thus, we controlled age, gender, and self-construal. Self-construal was used as a control variable because different feelings of psychological reactance can be generated depending on an independent or interdependent consumer (Jonas et al., 2009). Independent self-construal consumers remain distinct from others because they try to meet their personal goals over the collective goals of in-groups, and they focus their attention on themselves and their own preferences and desires (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Interdependent self-construal consumers remain related to others because they try to meet groups’ goals over their own personal goals and they focus their attention on in-groups and the groups’ preferences and desires (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Self-construal was measured using D’Amico and Scrima’s (2016) scale with 10-items on a 7-point Likert scale, anchored from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Table 1 shows the items used as well as their item loadings and reliabilities.

Results

A summary of the key findings is provided in Table 2. We used univariate ANOVA to test our hypotheses that the impact of ad appeals on attitude towards the ad and brand depend on the type of message frame utilized. We found support for our hypothesis that for rational appeal, a gain-framed message will lead to a more favorable attitude toward the ad (M=6.22, SD=1.77) than a loss-framed message (M=5.31, SD=1.75), F(1, 69) = 4.74, p < .05. Thus, H1a was supported. In addition, we found that rational appeals with gain-framed messages lead to a more favorable attitude towards the brand (M=4.61, SD=1.20) than loss frame messaging F(1, 69) = 6.13, p < .05, supporting H1b.

Our argument that for negative emotional appeals, a loss-framed message (M=3.80, SD=1.66) will lead to a less favorable attitude toward the ad than gain-framed messages (M=3.85, SD=1.81, F(1, 72) = 0.02, p = .90) was not supported (H2a). Similarly, the hypothesis that for negative emotional appeal a loss-framed message (M=3.12, SD=1.43), gain-framed message will result in a less favorable attitude toward the brand (M=3.50, SD=1.73, F (1, 72) = 1.08, p = .30) was not supported (H2b).

With regards to positive emotional appeals, we argued that loss-framed messaging will lead to a more favorable attitude toward the ad, than a gain-framed message (H3a). The results show a moderately significant difference between participants’ attitude toward ad for the gain frame (M=6.33, SD=2.12) and the loss frame (M=5.43, SD=1.99) messaging conditions; F(1, 72) = 3.59, p = .06. However, the difference is opposite to the direction that was hypothesized . Hence, H3a is not supported. Similarly, H3b is not supported in that the results indicate that positive emotional appeals with gain frame messaging (M=5.25, SD=1.28) led to a more favorable attitude toward the brand than loss frame messaging (M=4.36, SD=1.38) and the difference was significant; F(1, 72) = 8.30, p < .05. Again, though the difference between the two conditions is significant, they are in the direction opposite to what was hypothesized.

Reactance for Rational Appeals

We followed Hayes’ (2017) 4-step process using Model 4 on PROCESS macro v3.3 (SPSS 25) to perform our mediation analyses. According to Hayes (2017), for a mediation hypothesis to be supported, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, ignoring the mediator, should be significant (step 1). Next, the impact of the dependent variable on the mediator should be significant (step 2) and the effect of the mediator, controlling for the independent variable should be significant (Step 3). Finally, in step 4 of the mediation test, the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable, while controlling for the mediator, should not be significant. In H4a, we hypothesized that reactance mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude towards the ad. The results indicate that the relationships in step 1 (b = -0.91, t(69) = -2.18, p < .05), step 2 (b = 0.35, t(69) = 2.36, p < .05), and step 3 (b = -2.09, t(68) = -9.22, p < .05) of the mediation process were significant. However, the relationship in step 4 was not significant (b = -0.17, t(68) = -0.60, p = .55). Therefore, reactance completely mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude toward ad, supporting H4a. We also tested whether reactance mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude towards the brand (H4b). The results of the mediation test show that the relationships in step 1 (b = -0.66, t(69) = -2.48, p < .05), step 2 ( b = 0.35, t(69) = 2.36, p < .05) and step 3 (b = -1.44, t(68) = -11.34, p < .05) are significant while that in step 4 are not (b = -0.15, t(68) = -0.92, p = .36). Therefore, H4b was supported because reactance completely mediates the relationship between message frames with rational appeals and attitude toward brand.

Further, we examine if reactance mediates the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward ad (H5a) and attitude toward brand (H5b). For H5a, the results show that step 1 ( b = -0.05, t(72) = -0.13, p = .90) and step 2 (b = 0.02, t(72) = 0.11, p = .91) of the mediation analysis were not significant but step 3 was significant (b = -1.52, t(71) = -10.79, p < .05). Therefore, H5a was not supported even though step 4 of the analysis was not significant (b = -0.02, t(71) = -0.07, p = .95). Therefore, reactance did not act as a mediator between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward ad. Thus, H5a was not supported. Findings from the analysis to examine if reactance mediates the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward brand (H5b) shows that the relationships in step 1 ( b = -0.38, t(72) = -1.04, p = .30) and step 2 ( b = 0.02, t(72) = 0.11, p = .91) were not significant. Step 3 was significant (b = -1.22, t(71) = -8.01, p < .05) and step 4 was not (b = -0.36, t(71) = -1.32, p = .19). Therefore, reactance did not mediate the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and attitude toward brand and H5b was not supported.

In H6a we stipulated that reactance does not mediate the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward ad. As noted earlier, Hayes’ (2017) process was used to test this assertion. The results of step 1 of the mediation analysis was moderately significant (b = -0.91, t(72) = -1.90, p = .06), step 2 (b = -0.48, t(72) = 2.96, p < .05) and step 3 ( b = -2.26, t(71) = -9.83, p < .05) and step 4 (b = 0.17, t(71) = 0.51, p = .61) was not significant. Therefore, reactance mediates the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward ad so, H6a is not supported. Similarly, the results of the analysis for the hypothesis that reactance does not mediate the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward brand (H6b) do not support H6b (Hayes, 2017). The findings of the mediation analysis indicate that step (b = -0.90, t(72) = -2.88, p < .05), step 2 (b = 0.48, t(72) = 2.96, p < .05), and step 3 (b = -1.41, t(71) = -8.94, p < .05) were significant which step 4 was not (b = -0.23, t(71) = -0.99, p = .32). Therefore, reactance completely mediates the relationship between message frames with positive emotional appeals and attitude toward brand. Hence, H6b is not supported.

Different sets of one-way ANCOVA were conducted to determine statistically significant differences between gain and loss message frames with all the appeals on attitude toward ad, controlling for self-construal, age, and gender. For rational appeal, there was a significant effect of message frame type on ad attitude after controlling for self-construal, F(2, 68) = 4.54, p < .05; age, F(2, 68) = 5.44, p < .05; and gender, F(2, 68) = 4.70, p < .05. Again, for positive emotional appeal, there was either a significant or moderately significant effect of message frame type on ad attitude after controlling for self-construal, F(2, 71) = 4.67, p < .05; age, F(2, 71) = 3.67, p = .06; and gender, F(2, 71) = 3.18, p = .08. For negative emotional appeals, however, there was no significant effect of message frame type on ad attitude after controlling for self-construal, F(2, 71) = 0.00, p = .95; age, F(2, 71) = 0.04, p = .83; and gender, F(2, 71) = 0.00, p = .96. Therefore, none of the variables were found to have any impact on the hypothesized relationships.

Conclusion

The results of this research show that, for rational appeals, consumers’ attitudes toward both the advertisement and the brand are significantly more positive when the message is gain-framed rather than loss-framed. For positive emotional appeals, a similar pattern was found: gain-framed messages led to more favorable ad and brand attitudes compared to loss-framed messages. However, for negative emotional appeals, no significant differences emerged between gain and loss frames.

The study also found that psychological reactance mediates the relationship between message frames and consumer attitudes in the context of rational and positive emotional appeals. Specifically, reactance was found to mediate the relationships between (1) message frames with rational appeals and ad attitude, (2) message frames with rational appeals and brand attitude, (3) message frames with positive emotional appeals and ad attitude, and (4) message frames with positive emotional appeals and brand attitude. Reactance did not mediate the relationship between message frames with negative emotional appeals and consumer attitudes.

Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this research was to examine the impact of the interactions between message frame and ad appeal. We assessed the impact of gain versus loss message frame within rational, negative emotional, and positive emotional advertising appeals on attitude toward ad and attitude toward brand. This research also examined the role of reactance as a mediator between message frames with the ad appeals and attitude toward ad, and also between message frames with the ad appeals and attitude toward the brand.

The first set of statistical tests examined the impact of gain versus loss message frame with rational advertising appeals on consumer attitudes. Rational advertising appeals directly present the factual information about a brand to the consumers with an intent to encourage their logical thinking and analysis (Stafford & Day, 1995). Since gain-framed messages highlight the benefits of using a brand, these messages could help build a logical acceptance for rational appeals. On the contrary, since loss-framed messages affirm the losses of not using a brand, these messages could create a contradictory effect for rational appeals. Hence, using gain-framed messages was hypothesized to lead to building more positive consumer attitudes than using loss-framed messages and the results of this study support this argument. Specifically, the results show that consumers’ attitudes are more positive for gain-framed messages as compared to loss-framed messages. This suggests that when consumers engage in analytical processing, message frames that align with rational appeals (i.e., emphasizing gains) strengthen persuasion by reinforcing cognitive consistency rather than introducing threat or reactance. These results are consistent with the concept of rational appeals, which are meant to provide logical explanations/reasons for buying a particular brand by providing specific characteristics/features of the brand. This finding aligns with Buda and Zhang (2000), who found that gain-framed messages tend to be more persuasive in contexts requiring analytical processing, and extends their work by showing that such effects also hold when combined with rational appeals in advertising. It was also hypothesized that reactance mediates this relationship, which was supported by data analysis.

The next set of statistical analyses examined the impact of gain versus loss message frame with negative emotional advertising appeals on consumer attitudes. Since loss-framed messages are negative in nature, they tend to create psychological reactance amongst consumers by threatening their freedom of brand choice (Reinhart et al., 2007). Using these messages for negative emotional appeals, such as sad appeals, that are meant to strike an emotional chord with the consumers, could multiply the negativity of message frames with the negativity of emotions and hence lead to less positive consumer attitudes. On the other hand, since gain-framed messages are positive in nature, they neither develop any threats nor reactance for consumers and hence could lead to more positive attitudes for negative emotional appeals. Thus, using gain-framed messages was hypothesized to lead to building more positive consumer attitudes than using loss-framed messages. However, data analysis did not support our hypotheses, and we found that there was no significant difference between consumers’ attitudes for gain-framed and loss-framed messages with negative emotional appeals. The mean valuations of gain-framed and loss-framed messages show that with both the message framing techniques, consumers attitudes are low toward the negative emotional ad and the brand advertised. In addition, results also showed that reactance did not mediate the above-mentioned relationships. This indicates that when emotional tone is strongly negative, emotional valence itself may dominate message framing effects, leading consumers to disengage rather than differentiate between gain and loss messages. This finding contrasts with Akbari (2015) and Khan and Sindhu (2015), who reported stronger effects for emotional appeals, suggesting that when the emotional valence is negative, message framing may lose its differential impact due to an overall avoidance response. This could indicate that the negative emotions in the ad appeal, even with a gain-framed message, may generate an overall negative feeling amongst the consumers and hence they do not form positive attitudes either toward the ad or the brand. In other words, no matter how the message is framed, i.e. gain or loss, consumers develop negativity due to the negative emotional appeal.

The final set of statistical tests examined the impact of gain versus loss message frame with positive emotional advertising appeals on consumer attitudes. Positive emotional appeals, such as happy appeal, are used to create a connection between the consumers and the brand on an emotional level and make them feel positive about the brand. Due to negativity bias (i.e. negative things, as compared to positive things, have more impact on a person’s psychological state), using a loss-framed message for a positive emotional appeal can make the ad more distinguishing and informational than using a gain-framed message (Maheswaran & Meyers-Levy, 1990). Hence, using loss-framed messages was hypothesized to lead to building more positive consumer attitudes than using gain-framed messages. Though the hypotheses were not supported, yet significant differences were found between consumers’ attitudes for gain-framed and loss-framed messages with positive emotional appeals. Specifically, consumers’ attitudes were more positive for gain-framed messages as compared to loss-framed messages. This suggests that when consumers are exposed to positive emotional appeals, gain frame may amplify affective congruence and perceived brand warmth, consistent with broaden-and-build theory (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001). Positive emotions appear to facilitate more open, flexible processing, making gain frames more effective in shaping favorable evaluations. The primary rationale behind expecting loss-framed messages to create more positive consumer attitudes as compared to gain-framed messages was the concept of negativity bias (Rozin & Royzman, 2001). However, the current findings resonate more closely with Fredrickson’s (2001) broaden-and-build theory, which suggests that positive emotions expand individuals’ cognitive and behavioral responses, leading them to evaluate gain-framed ads more favorably. Generally, companies use gain-framed messages to promote their products to consumers, but since a consumer daily comes across countless number of advertisements, it is difficult to pay attention to them all and more difficult to form attitudes toward them. However, if a loss-framed message is used, the ad/brand can become distinguishable due to the negativity bias and consumers can pay attention to it. In the current study, though an attempt was made to capture this effect through an experiment, yet these consumers were isolated from the real-world advertising “tidal wave” where they were only shown a single – positive emotional – advertisement and were forced to pay attention on it. When asked about their opinion on the ad and the brand, they found gain-framed messages to be more positive than loss-framed messages due to their overall higher positivity. This observation also supports Tsai’s (2007) view that message execution techniques, such as framing, interact with emotional content to influence how consumers interpret ad meaning.

Theoretical Contribution

This study makes several contributions to the academic literature by integrating and extending prior theoretical perspectives on message framing, psychological reactance, advertising appeals, and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Specifically, the research proposes and tests a model that unites these frameworks to explain how message frames and ad appeals jointly influence consumers’ attitudes toward the advertisement and the brand.

First, this study advances message framing research by demonstrating that gain-framed messages, when used with rational advertising appeals, result in more favorable consumer attitudes toward the ad and the brand than loss-framed messages. This finding reinforces the persuasiveness of the gain frame in contexts requiring cognitive elaboration, extending prior work (e.g., Buda & Zhang, 2000) and showing that such effects persist even when reactance processes are considered.

Second, this study contributes to the literature on emotional advertising and psychological reactance by revealing that, for negative emotional appeals, both gain- and loss-framed messages lead to similarly low consumer attitudes. This outcome suggests that the emotional valence of the appeal may overshadow the effects of message framing, indicating that emotions and frames can operate independently within an ad. This finding refines earlier assumptions that framing effects are universal and highlights boundary conditions for reactance theory in emotional advertising contexts.

Third, this research extends the broaden-and-build theory (B. L. Fredrickson, 2001) by examining how positive emotions interact with message frames. While the theory posits that positive emotions can undo negative effects and broaden individuals’ thought–action repertoires, our results show that when positive affect is relatively moderate (MHappy = 4.34 on a 7-point Likert scale), it may not be sufficient to counteract the negativity produced by loss frame. This insight identifies a potential boundary condition for the broaden-and-build process, suggesting that the “undoing effect” of positive emotions depends on their intensity.

Finally, this research contributes a novel integrative perspective by highlighting the coexistence and interaction of message frames and advertising appeals within a single advertisement. Prior studies have typically examined these elements in isolation; this study shows that their combined influence better explains variations in consumer responses. By identifying which framing strategies (gain or loss) are more effective for specific types of appeals (rational, negative emotional, and positive emotional), this research provides a more comprehensive theoretical framework for understanding advertising effectiveness.

Managerial Implications

This research offers insights for multiple stakeholders involved in communication design and evaluation. First, there is a significant difference in consumer behavior toward types of message frames for rational advertising appeals. Specifically, gain-framed messages lead to more positive ad attitudes and brand attitudes, as compared to loss-framed messages. For advertising companies while making rational ads, this means that consumers find gain-framed messages to be more informative and logical as compared to the loss-framed messages. Therefore, this research suggests that the advertisers should emphasize on benefits rather than losses when communicating product performance information.

Second, it seems even for negative emotional advertising, there is a little, if any, difference in consumer behavior toward types of message frames. The differences in consumers’ ad attitudes and brand attitudes between advertisements with gain-framed messages and loss-framed messages seem to be insignificant. For advertising companies, this means that regardless of the type of message frames used in a negative emotional ad, consumers develop a negative attitude toward the ad and the brand. Even if a product in itself has negative emotions associated with it (for example, a pain medicine), advertisers should do what they can to avoid the negative emotional appeals in the advertisement of the product. This can be achieved by showing the positive emotional consequences of using the product, rather than showing a situation before the use of the product. For example, an ad might show someone relieved of pain medicine, rather than showing them in pain.

Thirdly, for positive emotional appeals, gain-framed messages lead to more positive consumer attitudes toward the ad and the brand, as compared to loss-framed messages when consumers are made to pay attention to the advertisements. Though, due to the limitations of the experimental design of this study, it remains unclear if these results would hold good for regular commercial advertisements, yet there are some important managerial implications of these results that cannot be ignored. This finding is important for managers because in recent days companies/advertisers are trying to find ways for consumers to pay more attention to ads and thus are using different media channels, like social media, video streaming, or games, to promote their products. In such cases, the current research findings would suggest that advertisers use gain-framed messages, and not loss-framed messages, when they are using such positive emotional appeals for their advertisements. However, for the advertisement appeals that highly enhance the positive emotions, those emotions can undo the effect of negativity created by loss frame and hence both, gain and loss frames, can be used.

Further, this study offers insights to marketing research agencies as well. The results highlight the importance of testing not only message content but also its framing appeals. Understanding psychological reactance and measuring it in pretests can help anticipate resistance and refine campaigns before launch.

Additionally, non - profit or public safety organizations, such as those promoting safe driving behaviors, the findings suggest that messages emphasizing positive outcomes like safety, protection and peace of mind may be more effective than fear or loss based appeals that highlight crashes and fatalities. Emphasizing benefits of compliance may lower psychological reactance and increase message acceptance among the target audience.

Limitations and Future Research

Any study must acknowledge limitations as well as future avenues of exploration. First, the experimental design used in the study limits the generalizability of this research. The controlled nature of the experiment means that consumers were interpreting these ads in isolation rather than in the context of the thousands of additional advertising stimuli they are exposed to each day, as well as through the lens of only one sort of advertising media (print ads), and one product category (tires). Hence, the experimental design limits the realism of this research in exchange for a controlled study of the phenomenon of interest. For future studies, researchers should expose participants to several advertisements, using various product types, in various forms of media communications to see if the relationships can be generalized across various contexts. Additionally, this research segregated advertising appeals by information, negative emotion, and positive emotion. Advertisements, however, can be a combination of informational/rational appeal and emotional (positive or negative) appeal. There can also be advertisements that consist of both positive and negative emotional appeals in the same ad. Finally, advertisements can have all three appeals at the same time as well. Future research can explore the effectiveness of message framing with all these combinations of appeals in a single advertisement.

Another limitation concerns the sample size and statistical power of the main study. Although the study design followed standard practices for experimental research, the overall sample size may not have provided sufficient statistical power for a 2x3 factorial design. Future research should aim to include larger samples to enhance the robustness of the findings and reduce the risk of any error.

Finally, while the manipulation checks for message frames and emotional appeal were statistically significant, the emotional appeal manipulation exhibited a smaller mean difference than expected. The moderate ratings of emotional intensity, particularly the relatively high mean for the loss-framed negative emotion condition, suggest that participants’ responses may have been influenced by individual differences in sensitivity or attentiveness. Future studies could employ additional pretesting, stronger or more nuanced emotional stimuli, and attention checks to further validate manipulation strength and ensure consistent participant engagement.

Additionally, the findings related to H2a and H2b may have been influenced by the intensity of the negative visual stimulus, which could have drawn attention away from the message text. While this issue does not invalidate the experimental results, it highlights an area for refinement in future research designs. Future studies may benefit from testing less extreme visual stimuli or varying message prominence to better isolate the effects of message framing. Moreover, although structural equation modeling (SEM) was considered as an alternative analytical approach, it was not adopted in the current study due to its larger sample size requirements and the study’s focus on direct and mediating effects through specific pairwise comparisons. Future research employing larger samples could use SEM to model these relationships more comprehensively.